Research - International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences ( 2023) Volume 12, Issue 7

Exploring Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN) in Cancer Patients at a Tertiary-Care Hospital: Incidence, Symptoms and Risk Factors

Wesam S. Abdel-Razaq1,3*, Shmeylan A. Alharbi1,2,3, Afnan M. Ibn Khamis1, Amal H. Alnahdi1, Amirah S. Alghanim1, Areej M. Almutairi1 and Hessa H. Alqahtani12King Abdulaziz Medical City, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh 11426, Saudi Arabia

3King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh 11481, Saudi Arabia

Wesam S. Abdel-Razaq, College of Pharmacy, King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs, Riyadh 14611, Saudi Arabia, Email: razaqw@ksau-hs.edu.sa

Received: 20-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. ijmrhs-23-103228; Editor assigned: 22-Jun-2023, Pre QC No. ijmrhs-23-103228(PQ); Reviewed: 04-Jul-2023, QC No. ijmrhs-23-103228(Q); Revised: 06-Jul-2023, Manuscript No. ijmrhs-23-103228(R); Published: 22-Jul-2023, DOI: -

Abstract

Background: Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN) is a common adverse effect experienced by cancer patients receiving neurotoxic chemotherapy. The present study aimed to explore the incidence, symptoms, and risk factors associated with CIPN in cancer patients upon the completion of anticancer therapy. Study design: The European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-CIPN20), implemented explicitly for cancer patients, was used to assess CIPN symptoms and severity. This survey evaluates CIPN symptoms related to three domains: sensory, motor, and autonomic functions. Results: A total of 357 patients’ records were included with a median age of 53.0 years (range 15-90). The most reported symptoms among respondents were tingling and numbness in the upper and/or lower extremities, which ranged from 57.1% to 65.5%. Shooting/burning pain in hands and feet was reported in 36.7% and 40.1%, respectively. Both motor and autonomic domains show significantly higher overall scores in females than males. In addition to the female gender, significantly worse sum scores of all domains were also observed in elderly patients, and in patients with low education levels, allergy history, and co-morbidities. Patients with metastatic cancer undergoing chemotherapy treatment have experienced a significantly increased severity of CIPN symptoms. Although many participants experience CIPN, over 70% of patients did not receive any pharmacological treatment for their symptoms or complaints. Conclusion: The study showed that many cancer patients had varying degrees of CIPN and were not optimally treated. Worse symptoms were observed in females, elderly patients, and metastatic cancer receiving chemotherapy

Keywords

Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN), Cancer patients, EORTC QLQ-CIPN20

Introduction

Many therapeutic modalities in cancer treatment have successfully tamed numerous malignancies and significantly improved cancer patients’ overall survival rates. Despite those reasonably recent treatment advances, cancer chemotherapies are still associated with substantial side effects, negatively impacting therapeutic outcomes that sometimes require chemotherapy delays or dose reduction [1]. Chemotherapy-Induced Peripheral Neuropathy (CIPN) is a common neurotoxic adverse event affecting cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment that can deleteriously compromise their quality of life [2].

CIPN is a set of sensory symptoms, of still debatable mechanism, caused by direct peripheral neuronal toxicity predominantly manifested as excruciating burning or shooting pain, tingling, and numbness in the arms, hands, legs, and feet, occasionally accompanied by motor weakness in the affected areas and autonomic changes of varying intensity and duration [3]. According to the published data, the prevalence of CIPN among cancer patients is approximately 30% to 40% of those treated with neurotoxic chemotherapeutic agents [4]. However, the incidence of CIPN is likely higher than reported rates in most studies, ranging from 19% to 85% [5]. The CIPN prevalence would be related to the number of cycles and type of chemotherapy drugs used rather than the cancer type [4]. Many chemotherapy drugs have been associated with the development of CIPN in cancer patients, such as platinum-based agents, taxanes, and vinca alkaloids [6]. Other therapeutic modalities have also been reported to be accompanied by peripheral neuropathies, including surgery or radiation [7]. Concomitant factors or conditions like viral infections, diabetes, vitamin deficiency, genetic factors, and autoimmune disorders have also been recognized to precipitate or exacerbate the risk of neuropathy in cancer patients [8, 9].

The present study aimed to explore the incidence, risk factors, and patterns of CIPN symptoms in cancer patients upon the completion of anticancer therapy. Moreover, it is pivotal to identify major risk factors among cancer patients associated with increasing severity of CIPN symptoms and explore whether cancer patients used any intervention in managing CIPN symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study was conducted at King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC) and King Abdullah Specialized Children’s Hospital (KASCH), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Ongoing cancer patients receiving chemotherapy or who have completed their treatment within the past three months attending the oncology, hematology, palliative, or ambulatory care clinics were approached personally and asked to participate in this study. Upon consent, eligible adult patients were invited to complete the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-CIPN20) [10]. This study was reviewed by the medical ethics committee and approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. (Reference number: IRBC/0463/22). Data were collected over a period of four months (from April 2022 to August 2022). No names or unrelated personal data were requested.

The EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 Survey

The EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 survey consists of a 20-item that evaluates patients’ experience and assesses the severity of CIPN symptoms in patients during the past week of completing the study. This questionnaire-based survey tool comprises three subscales that evaluate symptoms related to three domains: sensory, motor, and autonomic functions. The sensory scale includes nine items concerning tingling, numbness, shooting/burning pain, instability when walking or standing, distinguishing temperature, and hearing difficulty. The motor scale contains eight items about cramps, writing difficulty, manipulating small objects, and limb weakness. And the autonomic scale covers three items regarding changes in autonomic functions, including dizziness due to changing position, blurred vision, and erectile dysfunction (the last item was excluded in women). The scoring of the EORTC-CIPN20 survey tool is based on a numerical rating with a 4-point Likert scale (1=Not at all, 2=A little, 3=Quite a bit, and 4=Very much). All items and subscale sum scores were linearly converted to a percentage scale (0% to 100%), with higher scores representing worse symptoms or more extensive complaints.

Statistical Analysis

Results of continuous variables are summarized as mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) with medians and range, and categorical variables are expressed as frequencies or proportions of the total number of responses to the questionnaire items. Descriptive and statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Version 9.0 Software Package to evaluate the association between collected information and participants’ characteristics (variables). Statistical significance is considered at p-values less than 0.05.

Results

Demographics

A total of 398 questionnaires were completed out of 471 distributed, corresponding to an overall response rate of 84.5%. However, 41 records were excluded due to incomplete data. Hence, 357 patients’ records were included in the present study. The mean age of respondents was 51.9 years ± 14.1 years, with a median value of 53.0 years (range 15-90). More than 65% of them were less than 60 years of age. Most patients were non-smokers (78.7%). Female patients (n=222, 62.2%) constituted the majority of participants who were more obliging to the data collectors than male patients (n=135, 37.8%). This could perhaps reflect the conservative mind-set among male patients, or they were reluctant to share their suffering or disease-related experience. Table 1 displays the general profile and cancer characteristics of the participating cancer patients. The most reported cancer type was breast cancer, followed by hematologic and colorectal cancer (28.0%, 22.7%, and 16.0%, respectively). Most participants reported a non-metastatic status of their carcinomas (59.6%). The vast majority of patients have received cancer chemotherapy as the primary cancer treatment (94.4%).

| Variable | Value n (%) |

|---|---|

|

Age (in years) |

|

| Less than 20 | 7 (2.0%) |

| 20-59 | 228 (63.9%) |

| 60 and more | 122 (34.2%) |

|

Gender n (%) |

|

| Male | 135 (37.8%) |

| Female | 222 (62.2%) |

|

Tobacco smoker n (%) |

|

| Never smoked | 281 (78.7%) |

| Former | 56 (15.7%) |

| Current | 20 (5.6%) |

|

Marital Status n (%) |

|

| Single (never married) | 30 (8.4%) |

| Married | 269 (75.4%) |

| Divorced | 14 (3.9%) |

| Widowed | 44 (12.3%) |

|

Education Level n (%) |

|

| Uneducated (but can read) | 61 (17.1%) |

| Primary education | 93 (26.1%) |

| Secondary education | 97 (27.2%) |

| University graduate | 106 (29.7%) |

|

Work Status n (%) |

|

| Student | 12 (3.4%) |

| Unemployed | 182 (51.0%) |

| Employed | 85 (23.8%) |

| Retired | 78 (21.8%) |

|

Body BMI n (%)a |

|

| < 18.5 (underweight) | 21 (6.1%) |

| 18.5-24.9 (healthy weight) | 126 (36.3%) |

| 25-29.9 (overweight) | 117 (33.7%) |

| ≥ 30 (obesity) | 83 (23.9%) |

| Missing data=10 | |

|

Allergy n (%) |

|

| No | 294 (82.4%) |

| Yes (food or drugs) | 40 (11.2%) |

| Don’t know | 23 (6.4%) |

|

Type of cancer n (%) |

|

| Breast cancer | 100 (28.0%) |

| Colorectal cancer | 57 (16.0%) |

| Blood Cancer | 81 (22.7%) |

| Lung cancer | 29 (8.1%) |

| Liver cancer | 19 (5.3%) |

| Others | 71 (19.9%) |

| Metastatic status n (%) | |

| Metastatic | 92 (25.8%) |

| Non-Metastatic | 189 (52.9%) |

| Don’t know | 76 (21.3%) |

| Cancer treatment received n (%)a | |

| Surgery | 154 (43.1%) |

| Radiation | 155 (43.4%) |

| Chemotherapy | 337 (94.4%) |

| Interval since therapy (in weeks) | |

| Mean ± (SD) | 38.9 ± (46.0) |

| Median (range) | 20.0 (1-208) |

| Missing data=9 | |

| Past Medical History (Comorbidities) n (%)a | |

| None | 126 (35.3%) |

| Diabetes | 94 (26.3%) |

| Hypertension | 86 (24.1%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 50 (14.0%) |

| Arthritis | 48 (13.4%) |

| Cancer (previously) | 44 (12.3%) |

| Heart diseases | 29 (8.1%) |

| Thyroid Dysfunction | 24 (6.7%) |

| Depression | 13 (3.6%) |

| Others | 40 (11.2%) |

| Cancer Family History n (%) | |

| No | 249 (69.7%) |

| Yes | 107 (30.0%) |

| Missing data=1 | |

| Cancer Family History (relation) n (%)b | |

| Fathers or Mothers | 44 (41.1%) |

| Brothers or Sisters | 28 (26.2%) |

| Uncles or aunts | 29 (27.1%) |

| Grandparents | 13 (12.1%) |

| Sons or daughters | 12 (11.2%) |

| Others | 16 (15.0%) |

|

a Percentages are calculated out of the total participants (357 patients) |

|

|

b Percentages are calculated out of those who have a cancer family history (107 patients) |

|

EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 Survey Scores

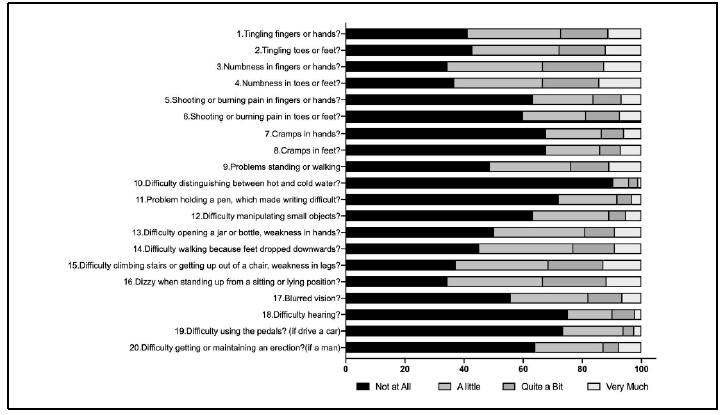

Figure 1 shows the distribution of EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 survey responses of the enlisted 20-item scale value (%). The most commonly reported symptoms among participants were tingling and numbness in the upper and/or lower extremities, which ranged from 57.1% up to 65.5%. Moreover, weakness in the legs and dizziness were among the most reported complaints in most participants, which were reported by 62.7% and 65.5%, respectively. Shooting or burning pain in hands and feet was reported in 36.7% and 40.1%, respectively. However, the infrequently reported symptom was difficulty distinguishing between hot and cold water, barely reported by 9.5% of participants. All other items were often reported ranging between 24.9% and 54.0%. According to the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 tool results, a minimum of 4.2% of the participants described at least one symptom or problem that disturbed them quite a bit or very much during the past week.

The overall mean scores ± (SD) with median and (range) of the three subscales (sensory, motor, and autonomic domains), the enlisted single 20-item, and the mean sum score scale of the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 survey are summarized in Table 2. For the sensory domain, the mean overall score (± SD) was 25.2% (20.8), ranging between 0% to 85.2% for men and between 0% to 100% for women, with an average mean difference of 2.6% (p = 0.250), which is not quite statistically significant. However, for the motor domain, the mean overall score (± SD) was 21.8% (21.5), ranging between 0 and 70.8% for men and between 0 and 100% for women, with an average mean difference of 6.2% (p=0.008). Except for item 19, “having difficulty using the pedals,” all mean scores of other motor scale items are noticeably higher (i.e., worse symptoms) in females than males. Four out of the eight items of the motor domain were shown to be statistically significant, including “cramps in hands”, “difficulty manipulating small objects with fingers”, “difficulty opening a jar or bottle because of weakness in hands”, and “difficulty walking because of feet dropped downwards”. Moreover, for the autonomic domain, the mean overall score (± SD) was 29.4% (26.3), ranging between 0 and 100% for both men and women, with an average mean difference of 6.6% (p=0.021). This difference is attributed to the substantially higher mean score value of item 17, “blurred vision”, which is considered very statistically significant (p=0.009). The prominent statistically significant differences in the motor and autonomic domains are also explicitly evident in the sum score of all domains. Compared with men, women scored statistically significantly higher (i.e., worse) sum score value with an overall mean (± SD) of 26.0% (20.7) and 21.5% (16.6) for women and men, respectively (p=0.033).

| EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 Item Number | Mean ± (SD) | p-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Men (n=135) | Women (n=222) | ||

| Sensory scale (9 items: tingling, numbness, pain, instability when walking or standing, distinguishing temperature, and hearing difficulty) | 25.2% (20.8) | 23.6% (19.1) | 26.2% (21.8) | 0.253 |

|

1. Have tingling fingers or hands? |

32.4% (33.7) |

29.4% (31.3) |

34.2% (35.0) |

0.192 |

|

2. Have tingling toes or feet? |

32.3% (34.5) |

31.1% (31.9) |

33.0% (36.0) |

0.614 |

|

3. Have numbness in your fingers or hands? |

37.2% (34.1) |

35.8% (33.2) |

38.0% (34.6) |

0.567 |

|

4. Have numbness in your toes or feet? |

37.0% (35.3) |

35.8% (33.5) |

37.7% (36.4) |

0.622 |

|

5. Have shooting or burning pain in your fingers or hands? |

19.9% (30.5) |

17.8% (27.3) |

21.2% (32.3) |

0.308 |

|

6. Have shooting or burning pain in your toes or feet? |

22.0% (31.5) |

18.3% (27.2) |

24.3% (33.7) |

0.081 |

|

7. Have problems standing or walking because of difficulty feeling the ground under your feet? |

28.7% (33.9) |

26.4% (31.6) |

30.0% (35.3) |

0.332 |

|

8. Have difficulty distinguishing between hot and cold water? |

4.9% (16.9) |

4.4% (16.7) |

5.3% (17.0) |

0.626 |

|

9. Have difficulty hearing? |

12.3% (24.0) |

13.3% (24.5) |

11.7% (23.8) |

0.543 |

| Motor scale (8 items: cramps, writing difficulty, manipulating small objects, and weakness) | 21.8% (21.5) |

17.9% (18.0) |

24.1% (23.0) |

0.008** |

|

10. Have cramps in your hands? |

17.2% (29.0) |

12.8% (25.4) |

19.8% (30.7) |

0.027* |

|

11. Have cramps in your feet? |

17.7% (30.0) |

14.8% (26.6) |

19.5% (31.9) |

0.152 |

|

12. Have a problem holding a pen, which made writing difficult? |

13.1% (24.2) |

12.8% (21.5) |

13.2% (25.7) |

0.878 |

|

13. Have difficulty manipulating small objects with your fingers (for example, fastening small buttons)? |

17.6% (27.5) |

13.8% (22.1) |

20.0% (30.2) |

0.039* |

|

14. Have difficulty opening a jar or bottle because of weakness in your hands? |

26.0% (31.9) |

19.8% (27.7) |

29.7% (33.7) |

0.004* |

|

15. Have difficulty walking because your feet dropped downwards? |

28.9% (32.2) |

23.5% (27.3) |

32.3% (34.5) |

0.012* |

|

16. Have difficulty climbing stairs or getting up out of a chair because of weakness in your legs? |

35.7% (34.5) |

31.1% (32.1) |

38.4% (35.7) |

0.052 |

|

17. Have difficulty using the pedals? (If driving a car)b |

11.7% (22.4) |

13.4% (21.9) |

9.2% (22.9) |

0.088 |

| Autonomic scale (3 items: dizziness due to changing position, blurred vision, and erectile dysfunction) | 29.4% (26.3) |

25.3% (21.2) |

31.9% (28.7) |

0.021* |

| 33.3% (0-100) |

22.2% (0-100) |

33.3% (0-100) |

||

|

18. Were dizzy when standing up from a sitting or lying position? |

36.9% (33.7) |

35.6% (31.3) |

37.7% (35.1) |

0.569 |

|

19. Have blurred vision? |

22.9% (30.4) |

17.5% (25.7) |

26.1% (32.6) |

0.009** |

|

20. Have difficulty getting or maintaining an erection? (If man)b |

18.8% (30.2) |

18.8% (30.2) |

NA | NA |

| Sum score | 24.3% (19.3) |

21.5% (16.6) |

26.0% (20.7) |

0.033* |

|

a Statistical significance is calculated by the unpaired t-test (* < 0.05 statistically significant, ** < 0.01 very statistically significant). |

||||

|

b Percentages are calculated for patients’ responses when applicable only. |

||||

Table 3 displays the mean scores ± (SD) of the three subscales (sensory, motor, and autonomic domains) of the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 survey in contrasting subgroups of participants. In addition to the female gender, several significant differences were also revealed among patients’ variables with high scores (i.e., worse symptoms), including elderly ages, being widowed, low education level, allergy history, co-morbidities, metastatic status, and chemotherapy medication.

| Variable | Sensory scale | Motor scale | Autonomic scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± (SD) | Mean ± (SD) | Mean ± (SD) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male (n=135) | 23.6% (19.1) | 17.9% (18.0) | 25.3% (21.2) |

| Female (n=222) | 26.2% (21.8) | 24.1% (23.0)** | 31.9% (28.7)* |

| Age (in years) | |||

| Less than 51 (n=162) | 23.8% (20.5) | 19.2% (20.3) | 30.3% (25.6) |

| 51 or more (n=195) | 26.3% (21.1) | 23.8% (22.2)* | 28.6% (26.8) |

| Tobacco smoker | |||

| No (n=281) | 25.0% (20.9) | 21.8% (21.6) | 29.8% (27.2) |

| Yes (current, former) (n=76) | 26.1% (20.7) | 21.6% (20.9) | 28.1% (22.6) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single (n=30) | 12.7% (16.4)** | 9.6% (14.9)*** | 25.7% (27.9) |

| Married (n=269) | 26.0% (20.2) | 21.3% (20.7) | 28.4% (24.7) |

| Divorced (n=14) | 26.5% (27.3) | 21.9% (21.3) | 26.2% (27.5) |

| Widowed (n=44) | 28.6% (22.8) | 32.7% (25.1)** | 39.1% (32.1) |

| Education level | |||

| Primary or less (n=154) | 26.1% (21.7) | 25.4% (22.7) | 30.7% (28.2) |

| Secondary or more (n=203) | 24.5% (20.2) | 19.0% (20.1)** | 28.4% (24.7) |

| Work Status | |||

| Student (n=12) | 8.0% (16.5)* | 12.3% (18.5) | 26.9% (30.0) |

| Unemployed (n=182) | 27.2% (21.7) | 24.8% (22.9) | 32.9% (28.9) |

| Employed (n=85) | 23.7% (18.4) | 19.7% (19.5) | 25.2% (21.7) |

| Retired (n=78) | 24.7% (20.7) | 18.3% (19.7) | 26.1% (22.8) |

| Body BMIa | |||

| < 25 (n=147) | 23.7% (19.3) | 21.9% (19.9) | 29.4% (23.6) |

| ≥ 25 (n=200) | 26.2% (21.8) | 21.6% (22.5) | 29.4% (28.0) |

| Allergy Historya | |||

| No (n=294) | 22.7% (19.3) | 19.0% (19.5) | 27.0% (24.7) |

| Yes (n=40) | 37.8% (23.8)*** | 32.2% (25.9)*** | 42.2% (31.9)*** |

| Cancer Family Historya | |||

| No (n=249) | 26.3% (20.3) | 22.7% (21.6) | 29.9% (25.8) |

| Yes (n=107) | 22.8% (22.0) | 19.7% (21.3) | 28.3% (27.5) |

| Other Morbidities | |||

| No (n=126) | 23.9% (20.7) | 17.7% (20.1) | 25.4% (22.1) |

| Yes (n=231) | 25.9% (20.9) | 24.0% (21.9)** | 31.6% (28.1)* |

| Cancer typea | |||

| Breast cancer (n=100) | 25.8% (23.4) | 24.4% (25.0) | 30.5% (26.1) |

| Other carcinomas (n=250) | 25.1% (19.9) | 20.6% (19.9) | 28.7% (26.1) |

| Metastatic Statusa | |||

| No (n=189) | 22.7% (18.4) | 18.2% (18.3) | 25.7% (23.1) |

| Yes (n=92) | 29.9% (23.6)** | 29.7% (26.4)*** | 39.1% (30.2)*** |

| Interval since treatment (in weeks)a | |||

| Less than 52 (n=263) | 24.5% (19.9) | 21.3% (20.9) | 27.9% (24.7) |

| 52 and more (n=85) | 27.0% (23.1) | 23.6% (23.7) | 33.1% (29.6) |

| Cancer interventions | |||

| Chemotherapy (n=337) | 25.8% (21.0) | 25.1% (21.7) | 29.8% (21.1) |

| No Chemotherapy (n=20) | 14.1% (15.3)* | 14.6% (15.7)* | 20.2% (22.8)* |

|

Statistical significance is calculated by the unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA test when applicable (* p<0.05 statistically significant, ** p<0.01 very statistically significant, *** p<0.001 extremely statistically significant). |

|||

|

a Patients who did not report were excluded. |

|||

Table 4 shows the severity of CIPN among participants. Cancer patients were classified into four grades according to the sum score of all domains of the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20. Generally, 53.5 % of patients were recognized to have moderate to severe symptoms of CIPN (grade 2-3). A similar tendency of grade distribution is exhibited among both genders. Over half of men and women reported grade 2-3 CIPN (50.4% and 55.4%, respectively). Patients with the highest CIPN grades reported significantly worse scores on all three subscales of EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 assessing sensory, motor, and autonomic symptoms compared to patients with lower CIPN grades (p ≤ 0.0001). Accordingly, participants were categorized into two groups: CIPN-negative (-CIPN) who had none to mild CIPN symptoms (with sum scores less than 33.4%), and CIPN-positive (+CIPN) who had moderate to severe CIPN symptoms. Patients experiencing shooting or burning pain in hands or feet associated with any intensity of tingling or numbness sensations were included in the +CIPN group

| Grades | Overall | Mena | Womena |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=135) | (n=222) | ||

| Grade 0 (No symptoms) | 33 (9.2%) | 12 (8.9%) | 21 (9.5%) |

| Grade 1 - Mild (score less than 33.4 %) | 133 (37.3%) | 55 (40.7%) | 78 (35.1%) |

| Grade 2 - Moderate (score 33.4% - 66.6%) | 176 (49.3%) | 66 (48.9%) | 110 (49.5%) |

| Grade 3 - Severe (score more than 66.6%) | 15 (4.2%) | 2 (1.5%) | 13 (5.9%) |

|

a Percentages are calculated out of the total number of men (n=135) or women (n=222). |

|||

Table 5 shows the univariate analysis of variables among cancer patients that may identify factors associated with CIPN. No significant difference was observed between males and females or in young and elderly patients. However, a significantly high proportion of single (never married) patients (73.3%) were recognized as -CIPN with RR=0.48; 95% CI: 0.26-0.87; p=0.016). In contrast, patients with food or drugs allergies and those who received chemotherapy treatment were associated with an increased risk of +CIPN (RR=1.34; 95% CI: 1.05-1.71; p=0.018 and RR=1.99; 95% CI: 1.01-3.91; p=0.046, respectively). None of the evaluated cancer types (breast, colorectal, blood, and lung cancers), cancer stage, or interval since the end of cancer therapy exhibited any significant difference between the two patient groups.

| Variable | +CIPN | −CIPN | RR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=191) | (n=166) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male (n=135) | 68 | 50.4 | 67 | 49.6 | 0.91 (0.74 to 1.12) | 0.362 |

| Female (n=222) | 123 | 55.4 | 99 | 44.6 | ||

| Age in years | ||||||

| Less than 60 (n=235) | 123 | 52.3 | 112 | 47.7 | 0.94 (0.77 to 1.15) | 0.537 |

| 60 and more (n=122) | 68 | 55.7 | 54 | 44.3 | ||

| Tobacco smoker | ||||||

| No (n=281) | 151 | 53.7 | 130 | 46.3 | 1.02 (0.80 to 1.30) | 0.865 |

| Yes (current, former) (n=76) | 40 | 52.6 | 36 | 47.4 | ||

| Marital Status a | ||||||

| Single (never married) (n=30) | 8 | 26.7 | 22 | 73.3 | 0.48 (0.26 to 0.87) | 0.015* |

| Married (n=269) | 148 | 55 | 121 | 45 | 1.13 (0.89 to 1.43) | 0.971 |

| Divorced (n=14) | 7 | 50 | 7 | 50 | 0.93 (0.55 to 1.59) | 0.796 |

| Widowed (n=44) | 28 | 63.6 | 16 | 36.4 | 1.22 (0.95 to 1.56) | 0.112 |

| Education Level a | ||||||

| Uneducated (can read) (n=61) | 33 | 54.1 | 28 | 45.9 | 1.01 (0.79 to 1.31) | 0.918 |

| Primary education (n=93) | 53 | 57 | 40 | 43 | 1.09 (0.88 to 1.35) | 0.422 |

| Secondary education (n=97) | 45 | 46.4 | 52 | 53.6 | 0.83 (0.65 to 1.05) | 0.118 |

| University graduate (n=106) | 60 | 56.6 | 46 | 43.4 | 1.08 (0.88 to 1.33) | 0.437 |

| Work Status c | ||||||

| Student (n=12) | 3 | 25 | 9 | 75 | 0.46 (0.17 to 1.23) | 0.121 |

| Unemployed (n=182) | 106 | 58.2 | 76 | 41.8 | 1.2 (0.99 to 1.46) | 0.069 |

| Employed (n=85) | 39 | 45.9 | 46 | 54.1 | 0.82 (0.64 to 1.06) | 0.128 |

| Retired (n=78) | 43 | 55.1 | 35 | 44.9 | 1.04 (0.83 to 1.31) | 0.741 |

| Body BMI b | ||||||

| < 25 (under and healthy) (n=147) | 80 | 54.4 | 67 | 45.6 | 1.02 (0.84 to 1.25) | 0.792 |

| ≥ 25 (over and obese) (n=200) | 106 | 53 | 94 | 47 | ||

| Allergy b | ||||||

| NK (n=294) | 148 | 50.3 | 146 | 49.7 | 1.34 (1.05 to 1.71) | 0.018* |

| Yes (food or drugs) (40=x) | 27 | 67.5 | 13 | 32.5 | ||

| Cancer type b | ||||||

| Breast cancer (n=100) | 57 | 57 | 43 | 43 | 1.09 (0.89 to 1.34) | 0.398 |

| Colorectal cancer (n=57) | 35 | 61.4 | 22 | 38.6 | 1.18 (0.94 to 1.49) | 0.162 |

| Blood Cancer (n=82) | 36 | 43.9 | 46 | 56.1 | 0.78 (0.60 to 1.02) | 0.066 |

| Lung cancer (n=29) | 14 | 48.3 | 15 | 51.7 | 0.89 (0.61 to 1.32) | 0.575 |

| Stage of Cancer b | ||||||

| Metastatic (n=92) | 54 | 58.7 | 38 | 41.3 | 1.14 (0.92 to 1.43) | 0.233 |

| Non-Metastatic (n=189) | 97 | 51.3 | 92 | 48.7 | ||

| Cancer treatment | ||||||

| Chemotherapy (n=337) | 201 | 59.6 | 136 | 40.4 | 1.99 (1.01 to 3.91) | 0.046* |

| Other interventions (n=20) | 6 | 30 | 14 | 70 | ||

| Interval since therapy (in weeks) b | ||||||

| Less than 52 (n=255) | 137 | 53.7 | 118 | 46.3 | 0.99 (0.80 to 1.25) | 0.995 |

| 52 or more (n=93) | 50 | 53.8 | 43 | 46.2 | ||

| Other Morbidities | ||||||

| No (n=126) | 63 | 50 | 63 | 50 | 0.9 (0.73 to 1.11) | 0.336 |

| Yes (n=231) | 128 | 55.4 | 103 | 44.6 | ||

|

+CIPN and −CIPN are Chemotherapy-Induced Neuropathy positive and negative, respectively. |

||||||

|

a Relative risks were calculated for individuals in each category relative to other patients. |

||||||

|

b Patients who did not report were excluded. |

||||||

Management and Additional Symptoms

Furthermore, 67.7% of patients had discussed their CIPN-related symptoms with their treating physicians. Though, over 70% of patients received no pharmacological treatment for such symptoms or complaints. The commonly used treatments were analgesics or vitamin B-complex. Almost one-third of patients (30.5%) turned to nonpharmacological therapies for managing their symptoms, including massage, supplements, and herbal medicines (Table 6).

| Questions | Value n (%) |

|---|---|

| Discussed any of the previous symptoms or complaints with the treating physician? | |

| No | 111 (32.3%) |

| Yes | 233 (67.7%) |

| Missing data=13 | |

| Received pharmacological therapy for previous symptoms or problems? | |

| No | 228 (70.2%) |

| Yes | 97 (29.8%) |

| Missing data=32 | |

| If yes, what type of pharmacological therapy was received? [n=97] a | |

| Vitamin B complex | 15 (15.5%) |

| Analgesics | 27 (27.8%) |

| Corticosteroids | 6 (6.2%) |

| Others (e.g., Vaseline, supplements, etc.) | 6 (6.2%) |

| Don’t know | 41 (42.3%) |

| Used any non-pharmacological therapy for previous symptoms or problems? | |

| No | 219 (69.5%) |

| Yes (ranging from 1 to 5 products) | 96 (30.5%) |

| Missing data=42 | |

| If yes, what type of non-pharmacological therapy was received? [n=96] a | |

| Acupuncture | 2 (2.1%) |

| Exercise | 17 (17.7%) |

| Herbal medicine | 19 (19.8%) |

| Massage/Footbaths | 37 (38.5%) |

| Vitamins | 18 (18.8%) |

| Omega-3 (fish oil) | 5 (5.2%) |

| Nutritional supplements | 25 (26.0%) |

| Others | 17 (17.7%) |

| How did you find out about the non-pharmacological therapy used? [n=89] a | |

| Friend/Family member | 36 (40.4%) |

| Another patient | 6 (6.7%) |

| TV/ Internet | 8 (9.0%) |

| Health care professional | 39 (43.8%) |

| Discussed non-pharmacological therapy with the treating physician? | |

| No | 94 (48.5%) |

| Yes | 100 (51.5%) |

| Missing data = 163 | |

| If discussed with your doctor, what was his/her reaction [n=100] a | |

| Supportive | 48 (48.0%) |

| Not Supportive | 21 (21.0%) |

| Neutral | 31 (31.0%) |

| Self-reported side effects during cancer chemotherapy | |

| None | 23 (6.4%) |

| Side Effects (ranging from 1 to 5 symptoms) | 334 (93.6%) |

|

a Patients who did not report were excluded. |

|

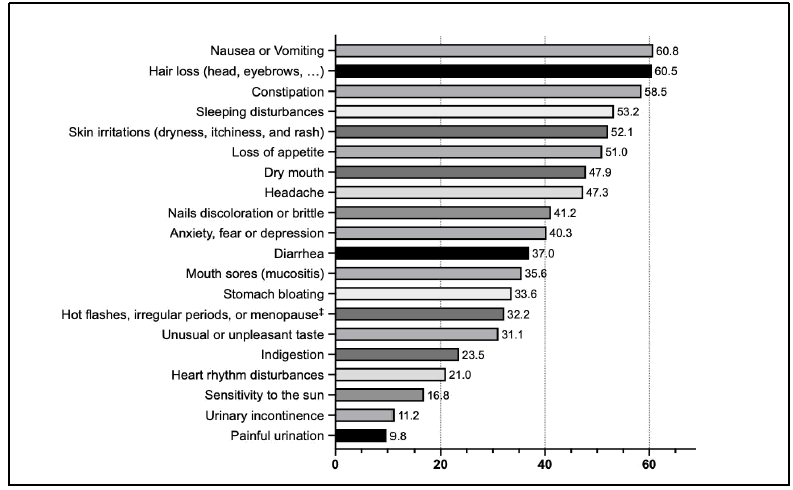

Finally, most participation reported additional side effects attributed to the chemotherapy used. Figure 2 shows the percentage of these disturbing side effects in descending order. Such ramifications were reported by more than 90% of patients, which ranges between 1 to 5 concurrent symptoms. More than 50% of participations reported nausea or vomiting, hair loss, constipation, sleep disturbances, skin irritations, and loss of appetite.

Discussion

CIPN is a common side effect experienced by cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Despite its clinical consequence and the widespread complaints among cancer patients receiving a variety of neurotoxic chemotherapy, the exact causes of CIPN are not fully understood [11]. Several methods have been used in clinical practice to evaluate the patients’ experience of CIPN. The most direct approach for assessing CIPN is the patient self-report, whereby the patient provides information about the location, intensity, and duration of their symptoms. A clinical examination can also be performed to assess the patient's neurological function, including their sensory, motor, and reflexes, to identify any specific deficits related to CIPN. Historically, several validated assessment tools were developed for assessing CIPN symptoms in cancer patients, including the neuropathic pain scale [12], and the quality of life scales such as the EORTC QLQ-C30 [13]. These instrument tools have been employed as the principal indicators for dose reduction or alteration of the treatment chemotherapy regimen due to the neurotoxicity adverse events and consequently in the symptom management [14]. However, the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 questionnaire-based survey has been developed as a brief version implemented explicitly for assessing the extent of symptoms and severity of CIPN in cancer patients [10].

The current study used the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 tool comprising three subscales that evaluate symptoms related to three domains: sensory, motor, and autonomic functions. Almost two-thirds of the cancer patients in the current study reported numerous CIPN symptoms. Most of them had moderate to severe CIPN symptoms. Shooting or burning pain in hands and feet was reported in approximately 30% of participants. Similar findings were reported in the published literature that assessed CIPN [15]. However, the most reported symptoms were mainly sensory (tingling and numbness) and motor (cramps and weakness), which are also consistent with several studies that may occasionally occur even in the absence of neuropathic pain symptoms [16].

The severity of neuropathy was measured according to the sum score of all domains of the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20. The severity of CIPN varies widely among participants. Over half of them had grade 2 or 3 CIPN (moderate to severe symptoms of CIPN) in both genders due to the chemotherapeutic agents used. Peculiarly, moderate to severe CIPN symptoms were even reported in 15% of cancer patients prior to the initiation of chemotherapy. Nonetheless, the incidence of CIPN in cancer patients who did not receive chemotherapy yet was minimal [17]. On the other hand, despite the non-statistically significant difference among patients with contrasting cancer types and/or stages, it is always important to consider the type of anticancer intervention used. Females and elderly patients were recognized as potential risk factors for the increased severity of CIPN among cancer patients in the present study. Similar findings have also been identified by several studies in addition to a number of other factors, particularly older age [18], chemotherapy cycles [19], African descent [20], diabetes mellites [21], and obesity [22]. However, other studies have failed to demonstrate such an association with CIPN [23, 24].

Currently, there is no standard treatment for CIPN in cancer patients, which can be most challenging as there is no one-size-fits-all approach. The most effective treatment that helps manage CIPN symptoms depends on the individual patient, the severity of symptoms, and the specific chemotherapy drugs they are receiving [25]. Various pain relievers such as acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids can help manage the pain associated with CIPN. However, long-term use of analgesics may lead to deleterious adverse effects and complications. Other treatments can also be used in managing symptoms associated with CIPN, which may involve certain antidepressants such as duloxetine and amitriptyline in addition to anticonvulsant medications such as gabapentin and pregabalin that can alter pain perception signalling [26]. Therefore, cancer patients need to communicate well with their healthcare providers to develop a safe and potentially effective management plan. Alternative therapies, such as capsaicin topical treatments and physical therapy, including exercise, massage, and acupuncture were also utilized by some patients, alone or in combination with other treatments, to reduce pain and other symptoms of CIPN [27, 28].

Even with these treatments, neuropathic symptoms might continue to persist beyond the cessation of chemotherapy [29]. Hence, the EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 instrument is a valuable tool for clinicians assessing CIPN symptoms that might help in optimizing an effective treatment plan with analgesics and other palliative treatments to reduce cancer patient complaints. Finally, although currently there is no effective cure for CIPN, management of CIPN symptoms, and pain in particular, with the available treatments, should be initiated early to avoid any interruption of the primary cancer therapy that can compromise the therapeutic outcome and eventually can deteriorate their quality of life.

Conclusion

A substantial number of participants were found to have moderate to severe CIPN. The mean scores of both motor and autonomic subscales of EORTC QLQ-CIPN20 were significantly higher (worse) in females and elderly patients than in the corresponding patient groups. Moreover, significantly higher (worse) scores on all three subscales (sensory, motor, and autonomic) were revealed in patients with metastatic cancer who received chemotherapy. Identifying risk factors associated with CIPN may help recognize at-risk patients, which could ultimately reduce their suffering and improve their quality of life if treated.

Declarations

Ethical Statement

This study did not receive any funding, but it was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of King Abdullah international medical research centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (IRB number: 0463/22). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their participation.

Author Contributions

• Conceived and designed the analysis: Wesam S. Abdel-Razaq, Shmeylan A. Alharbi

• Collected the data: Afnan M. Ibn Khamis, Amal H. Alnahdi, Amirah S. Alghanim, Areej M. Almutairi, Hessa H. Alqahtani

• Performed the analysis: Wesam S. Abdel-Razaq

• Wrote the paper: Wesam S. Abdel-Razaq, Afnan M. Ibn Khamis, Amal H. Alnahdi, Amirah S. Alghanim, Areej M. Almutairi, Hessa H. Alqahtani

• Writing-review and editing: Wesam S. Abdel-Razaq, Shmeylan A. Alharbi

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the whole team in the Oncology Department at KAMC and KASCH for their indispensable assistance during data collection.

References

- Selvy, Marie, et al. "Prevention, diagnosis and management of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a cross-sectional study of French oncologists’ professional practices." Supportive Care in Cancer, Vol. 29, 2021, pp. 4033-43.

Google Scholar Crossref - Bonhof, C. S., et al. "Painful and non-painful chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors: results from the population-based PROFILES registry." Supportive Care in Cancer, Vol.28, 2020, pp. 5933-41.

Google Scholar Crossref - Rivera, Donna R., et al. "Chemotherapy-associated peripheral neuropathy in patients with early-stage breast cancer: a systematic review." JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Vol. 110, No. 2, 2018, p. 140.

Google Scholar Crossref - Staff, Nathan P., et al. "Chemotherapy‐induced peripheral neuropathy: a current review." Annals of neurology, Vol. 81, No. 6, 2017, pp. 772-81.

Google Scholar Crossref - Zajączkowska, Renata, et al. "Mechanisms of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy." International journal of molecular sciences, Vol. 20, No. 6, 2019, p. 1451.

Google Scholar Crossref - Hu, Lang-Yue, et al. "Prevention and treatment for chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: therapies based on CIPN mechanisms." Current neuropharmacology, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2019, pp. 184-96.

Google Scholar Crossref - Kamgar, Mandana, et al. "Prevalence and predictors of peripheral neuropathy after breast cancer treatment." Cancer medicine, Vol. 10, No. 19, 2021, pp. 6666-76.

Google Scholar Crossref - Janahi, Noor M., et al. "Diabetic peripheral neuropathy, is it an autoimmune disease?." Immunology letters, Vol. 168, No. 1, 2015, pp. 73-79.

Google Scholar Crossref - Brizzi, Kate T., and Jennifer L. Lyons. "Peripheral nervous system manifestations of infectious diseases." The neurohospitalist, Vol. 4, No. 4, 2014, pp. 230-40.

Google Scholar Crossref - Postma, Tjeerd J., et al. "The development of an EORTC quality of life questionnaire to assess chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: the QLQ-CIPN20." European journal of cancer, Vol. 41, No. 8, 2005, pp. 1135-9.

Google Scholar Crossref - Kerckhove, Nicolas, et al. "Long-term effects, pathophysiological mechanisms, and risk factors of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathies: a comprehensive literature review." Frontiers in pharmacology, Vol. 8, 2017, p. 86.

Google Scholar Crossref - Trotti, Andy, et al. "CTCAE v3. 0: development of a comprehensive grading system for the adverse effects of cancer treatment." Seminars in Radiation Oncology, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2003.

Google Scholar Crossref - Mystakidou, Kyriaki, et al. "The EORTC core quality of life questionnaire (QLQ‐C30, version 3.0) in terminally ill cancer patients under palliative care: Validity and reliability in a Hellenic sample." International journal of cancer, Vol. 94, No. 1, 2001, pp. 135-9.

Google Scholar Crossref - Tan, Aaron C., et al. "Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy—patient-reported outcomes compared with NCI-CTCAE grade." Supportive Care in Cancer, Vol. 27, 2019, pp. 4771-7.

Google Scholar Crossref - Jones, Desiree, et al. "Neuropathic symptoms, quality of life, and clinician perception of patient care in medical oncology outpatients with colorectal, breast, lung, and prostate cancer." Journal of Cancer Survivorship, Vol. 9, 2015, pp. 1-10.

Google Scholar Crossref - Beijers, A. J. M., et al. "Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy in multiple myeloma: influence on quality of life and development of a questionnaire to compose common toxicity criteria grading for use in daily clinical practice." Supportive Care in Cancer, Vol. 24, 2016, pp. 2411-20.

Google Scholar Crossref - Boyette-Davis, Jessica A., et al. "Subclinical peripheral neuropathy is a common finding in colorectal cancer patients prior to chemotherapy." Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 18, No. 11, 2012, pp. 3180-7.

Google Scholar Crossref - Raphael, Michael J., et al. "Neurotoxicity outcomes in a population-based cohort of elderly patients treated with adjuvant oxaliplatin for colorectal cancer." Clinical Colorectal Cancer, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2017, pp. 397-404.

Google Scholar Crossref - Johnson, Cassandra, et al. "Candidate pathway-based genetic association study of platinum and platinum–taxane related toxicity in a cohort of primary lung cancer patients." Journal of the neurological sciences, Vol. 349, No. 1-2, 2015, pp. 124-8.

Google Scholar Crossref - Schneider, Bryan P., et al. "Genome-wide association studies for taxane-induced peripheral neuropathy in ECOG-5103 and ECOG-1199." Clinical Cancer Research, Vol. 21, No. 22, 2015, pp. 5082-91.

Google Scholar Crossref - Kus, Tulay, et al. "Taxane-induced peripheral sensorial neuropathy in cancer patients is associated with duration of diabetes mellitus: a single-center retrospective study." Supportive Care in Cancer, Vol. 24, 2016, pp. 1175-9.

Google Scholar Crossref - Ottaiano, Alessandro, et al. "Diabetes and body mass index are associated with neuropathy and prognosis in colon cancer patients treated with capecitabine and oxaliplatin adjuvant chemotherapy." Oncology, Vol. 90, No. 1, 2016, pp. 36-42.

Google Scholar Crossref - Schneider, Bryan P., et al. "Neuropathy is not associated with clinical outcomes in patients receiving adjuvant taxane-containing therapy for operable breast cancer." Journal of clinical oncology, Vol. 30, No. 25, 2012, p. 3051.

Google Scholar Crossref - Shah, Arya, et al. "Incidence and disease burden of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy in a population-based cohort." Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, Vol. 89, No. 6, 2018, pp. 636-41.

Google Scholar Crossref - Cleeland, Charles S., John T. Farrar, and Frederick H. Hausheer. "Assessment of cancer-related neuropathy and neuropathic pain." The Oncologist, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2010, pp. 13-18.

Google Scholar Crossref - Hou, Saiyun, et al. "Treatment of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: systematic review and recommendations." Pain Physician, Vol. 21, No. 6, 2018, p. 571.

Google Scholar - Kleckner, Ian R., et al. "Effects of exercise during chemotherapy on chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a multicenter, randomized controlled trial." Supportive Care in Cancer, Vol. 26, 2018, pp. 1019-28.

Google Scholar Crossref - Hao, Jie, Xiaoshu Zhu, and Alan Bensoussan. "Effects of nonpharmacological interventions in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: an overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses." Integrative cancer therapies, Vol. 19, 2020.

Google Scholar Crossref - Ibrahim, Eiman Y., and Barbara E. Ehrlich. "Prevention of chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: a review of recent findings." Critical reviews in oncology/hematology, Vol. 145, 2020.

Google Scholar Crossref