Research - International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences ( 2021) Volume 10, Issue 4

Health Education and Promotion Practices of Emergency Medicine Residents of Accredited Training Programs in the Philippines

Scarlett Mia S. Tabunar*Scarlett Mia S. Tabunar, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of the Philippines-College of Medicine/ Philippine General Hospital, Philippines, Email: sstabunar@up.edu.ph

, DOI: 0

Abstract

Objective: The Emergency Department (ED) is in a strategic position to recognize the major public health problems, identify underlying causes of diseases, and initiate targeted strategies to address the health-related behaviors that put individuals and communities at risk of adverse health outcomes. The objectives of this study were to describe the Health Promotion and Education (HPE) beliefs and practices of Emergency Medicine (EM) residents from accredited training programs in the Philippines.

Methods: Survey questionnaires were distributed to all the trainees as total enumeration was employed. Associations between qualitative variables were analyzed using Chi-square and Fischer’s exact test at a 95% level of confidence.

Results: Among the 203 residents, who answered the survey, mean age=31.06 ± 3.49, 54.68% were men and 70.44% were training in public hospitals. The EM physicians were recognized as the main providers of HPE activities at the ED. Residents who went on duty 6-7 days/week (p=0.013), worked at public hospitals (p=0.019) and saw mostly emergent and urgent patients (p=0.028) were significantly more prepared to counsel regarding health promotion and disease prevention. However, the overall performance of HPE activities at the ED was not associated with any demographic or working environment data. Despite the absence of several appropriate supports to perform HPE interventions, the majority of the EM residents still believed that behaviors promoting the health of an average person were important and they can successfully help change behaviors if given the proper support to implement the HPE interventions at the ED.

Conclusion: The current study recognized the role of EM physicians in delivering HPE activities at the ED and its importance despite the lack of support for its provision. It is therefore recommended that a more cohesive approach must be undertaken to incorporate HPE competencies in the EM training curricula, to arm residents with the needed public health knowledge and skills, and to make appropriate support in the ED readily available.

Keywords

Health promotion, Health education, Emergency medicine physicians, Beliefs, Practices, Training

Introduction

Emergency Departments (ED) are becoming important and unique venues for providing education on disease prevention and health promotion to a high-risk population seeking acute medical care. Although the focus of ED is generally to address an individual’s acute and urgent problem, it is strategically positioned to link the hospital specialist and the community. This places the Emergency Medicine (EM) physicians at the crossroads of a vital public health role by bridging biomedical treatments with the approaches for injury and disease prevention through strategies targeted at the community [1]. Public health interventions at the ED have been proposed for HIV testing, alcohol and tobacco abuse, domestic violence, and a host of injury prevention among vulnerable groups e.g. geriatric falls [2]. It has also been shown that these interventions have been successfully implemented in the ED and succeeding appropriate referrals result in patients’ satisfaction in some cases [3]. Halting the cycle of debilitating recurrent diseases would need addressing their underlying causes and this is where the partnership between emergency medicine and public health will be beneficial and synergetic. Currently, the constraints of ED resident doctors from providing public health interventions are due to the demands of their job of caring for the acutely ill and injured, scarce resources, limited time, and lack of experience in public health.

The Philippines suffers the “triple burden of disease”, with the mortality rates from Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) doubling in the last 50 years and accounting for 7 of the 10 leading causes of death. By classification of diseases, more than half of the 2012 Health Expenditure (HE) was spent on NCDs, followed by Communicable Disease (CDs) at more than a quarter. Injuries, resulting from rapid urbanization and industrialization, constitute only a small portion of the total HE at just 6 percent, but still substantial in absolute terms at about Philippine peso (Php) 30 billion (~USD 698 Million) [4]. This has resulted in rising ED utilization as reflected by increasing patient volume and overcrowding in emergency care facilities. It is a financial burden that impacts both individuals and the government, cost-effective solutions can be through promoting healthy lifestyles and preventive health measures. Clinical preventive services aimed at reducing behavioral antecedents of injuries and chronic diseases such as excessive alcohol use, obesity, and smoking provide a directed approach to further reduce morbidity and mortality. Sadly so, each patient encounter in the ED is a missed opportunity to educate patients on health preventive measures and promote healthy behaviors due to EM physicians disregarding their pivotal role. The specialty of EM is still a new field for medical practitioners and according to the Philippine Board of Emergency Medicine (PBEM), there are only 16 hospitals with accredited training programs last 2018 in the country with more than 100 million population [5]. A consensus within the EM specialty as to the role of emergency physicians in health promotion remains too small to be appreciated which also holds in the Philippines [6]. This study seeks to determine EM physician’s perception of their role in carrying out health education and promotion activities; describe current beliefs and practices, and identify consequent expectations and insights as to its future.

Methodology

Study Design and Population

This study employed a cross-sectional design and total enumeration with survey questionnaires distributed in November 2018 to all the residents (1st to 4th year) of accredited Emergency Medicine training programs of the Philippine Board of Emergency Medicine (PBEM). A total of 230 EM residents underwent formal residency training in 16 accredited hospitals all over the country according to the PBEM Secretariat at the start of the same year. Residents who opted not to answer the survey were excluded as participation in the study was purely voluntary.

The structured questionnaire was based on the objectives of the study and review of the literature and modified to make it appropriate to the local setting [6]. It was adapted from the tool used by Williams, et al. in the study on health promotion practices of emergency physicians which were founded from the survey of primary care practitioners developed by Wechsler, et al. [6,7]. The questionnaire consisted of 4 sections, namely, general data (age, sex, number of days on duty per week, hospital classification, daily average ED consults, and patient acuity); beliefs and perceptions of EM residents on health promotion behavior; current practices on health promotion; and EM resident’s confidence in counseling patients regarding behavior change. The hospital classification was either: (i) government health facility-those under the national government, Department of Health, local government unit, Department of Justice, State Universities and Colleges, government-owned and controlled corporations or (ii) private hospitals-those owned, established, and operated with funds from donation, principal, investment, or other means by any individual, corporation, association, or organization [8]. Patient acuity refers to how ill the patient is on arrival at the ED, their increased risk of clinical deterioration, and time consumed in the care needed, the 3-level triage system used were: (i) Emergent-those with life-threatening cases requiring immediate and rapid treatment, (ii) Urgent-those with significant medical problems that could be life-threatening, and (iii) Non-urgent-those with stable conditions and considered as non-medical emergencies [9-11]. To differentiate the resident’s performance of HPE activities and preparedness to counsel on the topic, descriptor responses under ‘always’ and ‘very’ were considered desirable outcomes, and those responses which fell under ‘somewhat’, ‘not’, ‘occasionally’ and ‘rarely/never’ were collapsed and interpreted as undesirable.

Socio-demographic data and qualitative data were encoded in Microsoft Excel and analyzed using STATA V12. These included the computation of frequencies, percentages, cross-tabulations, and means. Associations between qualitative variables of interest were analyzed using Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact test at a 95% level of confidence.

Ethical approval from the University of the Philippines-Manila Research Ethics Board (UPMREB 2018-370-01) was secured before the initiation of the study.

Results

A total of 203 residents answered the survey with a mean age of 31.06 ± 3.49, ranging from 26 to 43 years old. More than half (54.68%) were men, most were going on duty 3-5 days/week (71.43%) and 143 (70.44%) were training in government hospitals. The average daily patient consult was typically more than 101 (78.82%) which was mostly in the combined urgent (56.65%) and emergent (22.66%) acuity. The summary of the general characteristics of residents and ED patients seen is shown in Table 1.

| Data | n=203 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age (years) | Mean | 31.06 ± 3.49 (min=26; max=43) | ||

| n | % | |||

| 2. Sex | Male | 111 | 54.68 | |

| Female | 92 | 45.32 | ||

| 3. Number of days on duty per week at the ED | 1-2 days/week | 6 | 2.96 | |

| 3-5 days/week | 145 | 71.43 | ||

| 6-7 days /week | 52 | 25.62 | ||

| 4. Training Hospital Classification | Private | 60 | 29.56 | |

| Public | 143 | 70.44 | ||

| 5. Daily Average Consult at the ED | <50 consults/day | 13 | 6.4 | |

| 51-100 consults/day | 30 | 14.78 | ||

| >101 consults/day | 160 | 78.82 | ||

| 6. Acuity or Severity of Patient seen at ED | Emergent | 46 | 22.66 | |

| Urgent | 115 | 56.65 | ||

| Non-urgent | 38 | 18.72 | ||

| Mixed | 4 | 1.97 | ||

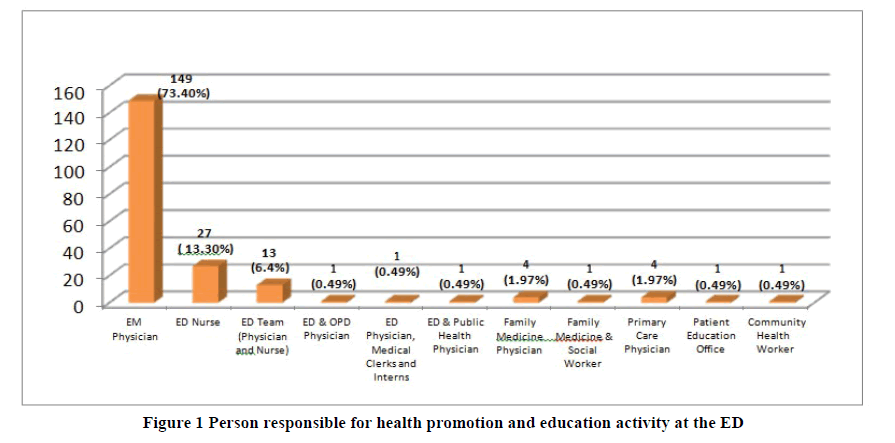

More than two-thirds (73.40%) of the respondents identified the Emergency Medicine physician and 13.30% stated that nurses as the majorly responsible to carry out patient education regarding health promotion at the emergency department (Figure 1).

Health Promotion Activities at the Emergency Department

The health promotion activities or interventions that were “always’ performed by EM physicians, as summarized in Table 2, were: making referrals for victims of abuse (67%), educating the patient on sexually transmitted illness (59.11%), educating the patient about reducing risk factors for injury (68.47%), educating patient about health risk factors (71.92%) and involving or motivating family members to participate in the patient’s health behavior (56.16%).

| Health Promotion Activity or Intervention | Always n (%) | Occasionally n (%) | Rarely/Never n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Make referrals for victims of abuse | 136 (67.00) | 47 (23.15) | 20 (9.85) |

| 2. Educate the patient on sexually transmitted illnesses | 120 (59.11) | 74 (36.45) | 9 (4.43) |

| 3. Educate the patient about reducing risk factors for injury | 139 (68.47) | 60 (29.56) | 4 (1.97) |

| 4. Educate the patient about health risk factors e.g. Smoking cessation, alcohol abuse, sedentary lifestyle, dietary modification | 146 (71.92) | 54 (26.60) | 3 (1.48) |

| 5. Educate patients about available resources in a community | 95 (46.80) | 90 (44.33) | 18 (8.87) |

| 6. Provide information on the effects of illicit drug use | 99 (48.77) | 92 (45.32) | 12 (5.91) |

| 7. Involve or motivate members of the family to participate in the patient’s health behavior | 114 (56.16) | 78 (38.42) | 11 (5.42) |

| 8. Ask the patient how much her or his health affects relationships with family, friends, and coworkers | 76 (37.44) | 87 (42.86) | 40 (19.70) |

Information on smoking (75.37%), alcohol use (76.35%), and illicit drug use (68.47%) were “routinely” gathered by EM doctors while that of the patient’s health practices on diet (67%), exercise (63.55%), domestic violence (56.16%), stress (58.13%) and sexual practices (64.045) were only occasionally asked during patient encounters at the ED (Table 3).

| Health Practice | Routinelyn (%) | Occasionally n (%) | Rarely/Never n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 153 (75.37) | 44 (21.67) | 6 (2.96) |

| Alcohol use | 155 (76.35) | 42 (20.69) | 6 (2.69) |

| Illicit drug use | 139 (68.47) | 59 (29.06) | 5 (2.46) |

| Diet | 50 (24.63) | 136 (67.00) | 17 (8.37) |

| Exercise | 36 (17.73) | 129 (63.55) | 38 (18.72) |

| Domestic violence | 30 (14.78) | 114 (56.16) | 59 (29.06) |

| Stress | 40 (19.70) | 118 (58.13) | 45 (22.17) |

| Sexual Practices | 45 (22.17) | 130 (64.04) | 28 (13.79) |

As to the preparedness of the EM Physicians in counseling patients regarding behavior change (Table 4), they reported they were ‘very prepared’ to advise patient on smoking (67%), alcohol use (65.52%), illicit drug use (59.61%) and diet (51.23%) while they admitted to being only “somewhat prepared” to counsel them regarding domestic violence (72.41%), stress (57.64%) and sexual practices (55.17%).

| Health-related behavior | Very prepared n (%) | Somewhat prepared n (%) | Not prepared n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 136 (67.00) | 66 (32.51) | 1 (0.49) |

| Alcohol use | 133 (65.52) | 68 (33.50) | 2 (0.99) |

| Illicit drug use | 121 (59.61) | 78 (38.42) | 4 (1.97) |

| Diet | 104 (51.23) | 93 (45.81) | 6 (2.96) |

| Exercise | 100 (49.26) | 96 (47.29) | 7 (3.45) |

| Domestic violence | 38 (18.72) | 147 (72.41) | 18 (8.87) |

| Stress | 68 (33.50) | 117 (57.64) | 18 (8.87) |

| Sexual Practices | 80 (39.41) | 112 (55.17) | 11 (5.42) |

Beliefs and Perception of EM Residents on Health Promotion and Education

Despite being prepared to counsel patients on four of the eight specific health-related behaviors, the EM trainees still perceived that they will only be “somewhat” successful in helping their patients achieve change on all the healthrelated behaviors which include smoking (70.94%), alcohol use (71.43%), illicit drug use (69.95%), diet (71.92%), exercise (76.35%), domestic violence (73.40%), stress (74.38%) and sexual practices (78.33%) (Table 5).

| Health-related behavior | Very Successful n (%) | Somewhat Successful n (%) | Not Successful n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 37 (18.23) | 144 (70.94) | 22 (10.84) |

| Alcohol use | 36 (17.73) | 145 (71.43) | 22 (10.84) |

| Illicit drug use | 33 (16.26) | 142 (69.95) | 28 (13.79) |

| Diet | 34 (16.75) | 146 (71.92) | 23 (11.33) |

| Exercise | 26 (12.81) | 155 (76.35) | 22 (10.84) |

| Domestic violence | 18 (8.87) | 149 (73.40) | 36 (17.73) |

| Stress | 24 (11.82) | 151 (74.38) | 28 (13.79) |

| Sexual Practices | 20 (9.85) | 159 (78.33) | 24 (11.82) |

The beliefs and perceptions on the different health-promoting behaviors were asked using a four-point scale on how important each of the behavior was in promoting the health of an average person. Most of the EM residents perceived that all the health-promoting behaviors were important. The combined frequencies of the “very” and “somewhat” important responses were all beyond 80% on all the health-promoting behaviors, detailed results are in Table 6.

| Health-Promoting Behavior | Very Important n (%) | Somewhat Important n (%) | Somewhat Unimportant n (%) | Very Unimportant n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eliminate cigarette smoking | 165 (81.28) | 29 (14.29) | 8 (3.94) | 1 (0.49) |

| Always use a seat belt when in a car | 170 (83.74) | 32 (15.76) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (0.49) |

| Avoid using illicit drugs | 191 (94.09) | 9 (4.43) | 1 (0.49) | 2 (0.99) |

| Drink alcohol moderately or not at all | 100 (49.26) | 89 (43.84) | 13 (6.40) | 1 (0.49) |

| Engage in moderate daily physical activity | 115 (56.65) | 84 (41.38) | 3 (1.48) | 1 (0.49) |

| Avoid excess caloric intake | 100 (49.26) | 87 (42.86) | 15 (7.39) | 1 (0.49) |

| Avoid foods high in saturated fats | 111 (54.68) | 74 (36.45) | 17 (8.37) | 1 (0.49) |

| Eat a balanced diet | 140 (68.97) | 56 (27.59) | 6 (2.96) | 1 (0.49) |

| Engage in aerobic activity at least 3 times a week | 96 (47.29) | 91 (44.83) | 14 (6.90) | 2 (0.99) |

| Avoid undue stress | 121 (59.61) | 68 (33.50) | 10 (4.93) | 4 (1.97) |

| Have an annual physical exam | 109 (53.69) | 80 (39.41) | 13 (6.40) | 1 (0.49) |

| Decrease salt consumption | 81 (39.90) | 104 (51.23) | 14 (6.90) | 4 (1.97) |

| Have a baseline exercise test | 78 (38.42) | 92 (45.32) | 29 (14.29) | 4 (1.97) |

| Minimize sugar intake | 91 (44.83) | 96 (47.29) | 12 (5.91) | 4 (1.97) |

| Responsible sexual practices | 144 (70.94) | 48 (23.65) | 9 (4.43) | 2 (0.99) |

Support Provision in the Implementation of HPE Activities at the ED

The survey also showed that not all forms of support to implement the HPE activities (Table 7) were present in the hospitals with accredited EM training programs. More than half of the EM doctors reported that an allocated time for counseling patients on health-related behavior (52.71%), funding for HPE activities (55.67%), and incentives on performing HPE interventions (65.02%) were non-existent in their EDs. On the other hand, a considerable percentage of them stated that appropriate resources e.g. Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) materials, access to electronic resources (72.41%), policies on health promotion (82.76%), didactics or learning activities on HPE (66.01%) and support from another specialty department (78.82%) were present in their hospitals to routinely perform HPE activities at the ED.

| Form of Support | Present n (%) | Not Present n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1.Allocated time for counseling patients on health-related behavior | 96 (47.29) | 107 (52.71) |

| 2.Funding for health promotion activities | 90 (44.33) | 113 (55.67) |

| 3. Appropriate resources e.g. Information, Education, and Communication (IEC) materials, access to electronic references | 147 (72.41) | 56 (27.59) |

| 4. Policies on health promotion | 168 (82.76) | 35 (17.24) |

| 5. Didactics or learning activities on health promotion and education e.g. Lectures on health promotion, inclusion in required terminal competencies | 134 (66.01) | 69 (33.99) |

| 6. Support from other specialty departments e.g. Surgery on injury prevention; Infectious Section on HIV screening etc.; Internal Medicine on smoking cessation, alcohol abuse, or diet restriction | 160 (78.82) | 43 (21.18) |

Interestingly, most of the EM physicians perceived that they will be “very” successful in effecting change on the different health-related behaviors of patients if given the appropriate support to carry out HPE interventions in their work area. Table 8 showed the results of the abovementioned findings.

| Health-related behavior | VerySuccessful n (%) | SomewhatSuccessful n (%) | Not Successful n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 120 (59.11) | 80 (39.41) | 3 (1.48) |

| Alcohol use | 117 (57.64) | 83 (40.89) | 3 (1.48) |

| Illicit drug use | 126 (62.07) | 69 (33.99) | 8 (3.94) |

| Diet | 120 (59.11) | 79 (38.92) | 4 (1.97) |

| Exercise | 114 (56.16) | 83 (40.89) | 6 (2.96) |

| Domestic violence | 99 (48.77) | 94 (46.31) | 10(4.93) |

| Stress | 108 (53.20) | 84 (41.38) | 11 (5.42) |

| Sexual Practices | 111 (54.68) | 87 (42.86) | 5 (2.46) |

Going on duty 6-7 days/week (p=0.013), working in public or government hospitals (p=0.019), and seeing mostly emergent and urgent patients (p=0.028) were significantly associated with the overall perception of preparedness to advise patients on HPE topics as shown in Table 9.

| General Characteristics | Categories/Levels | Overall Perception of Preparedness to Counsel | Test Statistic (Chi-square) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desirable (%) | Undesirable (%) | ||||

| Age | ≤ 30 years | 10 (8.62) | 106 (91.38) | 0.02 | 0.887 |

| >30 years | 8 (9.20) | 79 (90.80) | |||

| Sex | Male | 9 (8.11) | 102 (91.89) | 0.175 | 0.676 |

| Female | 9 (9.78) | 83 (90.22) | |||

| Year Level | 1st-2nd Year | 11 (8.27) | 122 (91.73) | 0.17 | 0.68 |

| 3rd-4th Year | 7 (10.00) | 63 (90.00) | |||

| Duty Days | ≤ 5 days/week | 9 (5.96) | 142 (94.04) | 6.164 | 0.013 |

| 6-7 days/week | 9 (17.31) | 43 (82.69) | |||

| Hospital Classification | Private | 1 (1.67) | 59 (98.33) | 5.465 | 0.019 |

| Public | 17 (11.89) | 126 (88.11) | |||

| Daily Average Consults | ≤ 100 consults | 4 (9.30) | 39 (90.70) | 0.013 | 0.91 |

| >100 consults | 14 (8.75) | 146 (91.25) | |||

| Acuity or Case Severity | Emergent/Urgent | 18 (10.91) | 147 (89.09) | - | 0.028 |

| Non-urgent | 0 (0.00) | 38 (100.00) | |||

However, the overall performance of HPE activities at the ED was not associated with any demographic data or working environment information of the EM residents, as shown in Table 10.

| General Characteristics | Categories/ Levels | Overall Perception of Preparedness to Counsel | Test Statistic (Chi-square) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desirable (%) | Undesirable (%) | ||||

| Age | ≤ 30 years | 18 (15.52) | 98 (84.48) | 2.38 | 0.123 |

| >30 years | 21 (24.14) | 66 (75.86) | |||

| Sex | Male | 23 (20.72) | 88 (79.28) | 0.359 | 0.549 |

| Female | 16 (17.39) | 76 (82.61) | |||

| Year Level | 1st Year | 10 (15.63) | 54 (84.38) | 2.077 | 0.557 |

| 2nd Year | 13 (18.84) | 56 (81.16) | |||

| 3rd Year | 11 (20.37) | 43 (79.63) | |||

| 4th Year | 5 (31.25) | 11 (68.75) | |||

| Duty Days | ≤ 5 days/week | 29 (19.21) | 122 (80.79) | <0.001 | 0.997 |

| 6-7 days/week | 10 (19.23) | 42 (80.77) | |||

| Hospital Classification | Private | 10 (16.67) | 50 (83.33) | 0.356 | 0.551 |

| Public | 29 (20.28) | 114 (79.72) | |||

| Daily Average Consults | ≤ 50 consults | 4 (30.77) | 9 (69.23) | 1.253 | 0.535 |

| 51-100 consults | 6 (20.00) | 24 (80.00) | |||

| >100 consults | 29 (18.13) | 131 (81.88) | |||

| Acuity or Case Severity | Emergent/Urgent | 35 (21.21) | 130 (78.79) | 2.272 | 0.132 |

| Non-urgent | 4 (10.53) | 34 (89.47) | |||

Discussion

Emergency physicians are in the key position to identify predisposing factors for risky health behaviors and implement public health strategies owing to the nature of their specialty. In this study, the majority of the respondents recognized that the EM physicians were primarily responsible for providing health education and health-promoting activities at the ED which was consistent with the findings of a similar investigation in 1998 [6]. Although, EM residents have reported performing health promotion activities most of the time during patient encounters, the extent to which they have routinely gathered data on health practices was not done. Emergency departments have proven to be effective settings for disease surveillance, risky health behavior screening, and initiation of intervention programs for HIV, falls, suicide, intimate partner violence, tobacco addiction, alcohol and drug abuse, injury, and chronic disease, it thus became imperative for doctors manning EDs to regularly ask information on patient’s health-related practices and administer HPE interventions when necessary [12].

More than half of the EM residents stated that they were “very prepared” to counsel patients on smoking, alcohol use, illicit drug use, and diet, better than the reported results of Williams, et al., where emergency physicians felt very prepared to advise patients only on smoking and alcohol [6]. But the preparedness did not translate to a perception of being successful in helping patients change all their deleterious behaviors on smoking, alcohol use, illicit drug use, domestic violence, stress exercise, diet, and sexual practices. Residents who went on duty 6-7 days/week, worked at public hospitals, and saw mostly emergent and urgent patients were more prepared to advise regarding health promotion and disease prevention. The residents gained more confidence in giving advice on health-related behaviors working more days at the ED that resulted in greater exposure to patients presenting with more complex illnesses and higher acuity. The overall performance of HPE activities at the ED was still not consistent and was neither associated with any neither demographic nor working environment profile. This supported the growing evidence that EM physicians still do not recognize their role in being advocates of health promotion and their missed opportunities on educating patients with appropriate information on disease prevention. A 2001 Canadian survey on emergency doctors also showed that ED physicians were less certain about the role of health promotion in EM, with respondents questioning the economic viability and practicality of HPE in an acute setting like the emergency room [13].

Despite the absence of allocated time, funding, and incentives for HPE interventions, the majority of the trainees still believed that behaviors promoting the health of an average person were essential and they can successfully effect change if provided the appropriate form of support to carry out the task. These have implications on the far-reaching potential of the EM specialty to be an advocate of HPE particularly for screening and surveillance at the level of emergency consult. Every ED visit is an opportunity for health front liners to recognize high-risk individuals and direct access to specialized care. Counseling provided by ED doctors is highly regarded and accepted by patients [14,15]. However, it was also noted that screening for underlying injury risk factors and other forms of risk reduction were not consistently performed and oftentimes neglected [16]. Several barriers were identified in the routine implementation of health promotion activities at the ED, among them were cost considerations associated with the integration of preventive services into the practice of emergency care and the low confidence and high pessimism of ED physicians to the success of HPE efforts. The lack of training and preparedness were often cited as reasons for not performing preventive interventions or giving home advice. The incorporation of HPE into the EM residency curriculum as well as the development of targeted continuing education is therefore highly recommended.

Additional impediments exist in implementing public health activities in the acute setting, these include increasing workload, financial pressures, and the belief that preventive medicine approaches should be relegated to doctor’s clinics, public health offices, and other non-ED sites [17]. To develop, evaluate and conduct effective programs, EM physicians need knowledge and skillsets in this area. Integration of these topics into the EM residency may be the ideal way which will also teach residents about the interconnectedness of hospital-based medicine and public health [18]. Emergency medicine’s role in delivering clinical preventive services has always been a source of debate and controversy [19]. Considered as a relatively young specialty, EM has been mostly defined by unscheduled acute care and crisis management that is often reflected in the scope of training programs. Residents have minimal experience in assessing the patient’s psychosocial or behavioral health risks and are thus not able to acquire skills in motivational interviewing. The provision of preventive services at the ED would involve competing for clinical priorities and constraints on time, resources, and compensation. Even strong supporters for HPE, while recognizing the health impact of unhealthy behaviors, knew that screening and intervention of any kind have been difficult at this venue. Furthermore, the EDs that treat the most vulnerable patients were the most stressed and were less likely to pay attention to low priority tasks. High-volume public hospital EDs with long queues, limited budgets, and insufficient staff will not have the resources to add HPE activities to their scope of duties and responsibilities [1].

At present, there remains no consensus within the specialty of emergency medicine as to the role of emergency physicians in health promotion and education [6]. Emergency doctors are often reluctant to become involved in public health interventions. Initiation of ED-based routine HIV screening drawn from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines were met by opposition and objections ranged from “it’s not part of my job” to “it takes too much time” and everything in between [20]. From the resident’s point of view, additional obligations imposed during their tour of duty can be daunting. Hsieh, et al. investigated resident attitudes and perceptions related to the implementation of HIV screening at the ED and found that most negative attitudes were related not to the idea of HIV screening but the operational components such as paperwork and staffing [21]. Residents support preventive efforts in theory but are limited by the reality of the work environment. If physicians are already overwhelmed and overstressed, added responsibility can lead them to dismiss a program regardless of its significance. The major concern in implementing ED-based public health initiatives in places with limited resources is that the ED will lose focus on the primary objective of providing quality care for the acutely ill. There is neither an established policy on the EM physician’s role in health promotion nor a compelling requirement exists for them to participate in one during the patient encounter as it is not part of the core competency of the EM specialty. To date, PBEM does not stipulate any public health activity in the terminal requisites for residents. To initiate health promotion programs at the ED, it is therefore worth considering the perspective of the residents as they are expected to be the driving force of these activities once they start private practice after EM training.

The major strengths of this study were a large number of respondents, 88.26% of the total EM resident population participated, and it is the first to be conducted regarding the topic. The use of a self-reported questionnaire to determine the performance of HPE activities was a possible limitation due to the response bias that may have been elicited. The behavior of interest was considered ideal and regarded as satisfactory; the responses may be skewed to the desirable descriptors and thus may not be a reliable measure of real practice. Overall, it has achieved in giving an evidencedbased picture of the health promotion and education beliefs and practices of EM residents in the country.

Conclusion

The Emergency Medicine physician was recognized as the main provider of health education and promotion activities at the ED but the extent to which they collected information on the health practices of their patients was not routinely done. The EM residents were generally very prepared to counsel patients on smoking, alcohol use, illicit drug use, and diet. Residents who went on duty 6-7 days/week, worked at public hospitals, and saw mostly emergent and urgent patients were more prepared to counsel regarding health promotion and disease prevention. Despite the absence of adequate support to perform HPE activities, the majority of the EM residents still believed that behaviors promoting the health of average individuals were paramount and they can successfully help change patient’s behaviors if given the provisions to implement the interventions at the ED. The overall performance of HPE activities at the ED remained not consistent and it was not associated with any demographic or working environment profile.

For the emergency department to be the ‘‘safety net’’ provider for the high-risk population that flock its doors, a more cohesive approach must be undertaken to arm residents with the needed public health knowledge and skills, to incorporate HPE competencies in the EM training program, and to make appropriate support readily available to ensure the performance of preventive services in the emergency setting.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Rhodes, Karin V., and Daniel A. Pollock. "The future of emergency medicine public health research." Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America, Vol. 24, No. 4, 2006, pp. 1053-73.

- Kit Delgado, M., et al. "Multicenter study of preferences for health education in the emergency department population." Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 17, No. 6, 2010, pp. 652-58.

- Rega, Paul P., et al. "The delivery of a health promotion intervention by a public health promotion specialist improves patient satisfaction in the emergency department." Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 19, No. 3, 2012, pp. 313-17.

- Ortiz, Danica Aisa P., and Michael RM Abrigo. "The triple burden of disease." Economic issue of the Day, 2017.

- Republic of the Philippines. "Commission on Population and Development" https://popcom.gov.ph/

- Williams, Janet M., Ann C. Chinnis, and Daniel Gutman. "Health promotion practices of emergency physicians." The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 18, No. 1, 2000, pp. 17-21.

- Wechsler, Henry, Sol Levine, and Roberta K. Idelson. "The physician's role in health promotion revisited-A survey of primary care practitioners." The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 334, 1996, pp. 996-98.

- Public Health Resources. "New DOH Hospital Classifications 2015." 2015. https://publichealthresources.blogspot.com/2015/04/new-doh-hospital-classifications-2015.html

- Recio-Saucedo, Alejandra, et al. "Safe staffing for nursing in emergency departments: Evidence review." Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 32, No. 11, 2015, pp. 888-94.

- Travers, Debbie A., et al. "Five-level triage system more effective than three-level in tertiary emergency department." Journal of Emergency Nursing, Vol. 28, No. 5, 2002, pp. 395-400.

- Jimenez, Ma Lourdes D., et al. "A descriptive study on the factors affecting the length of stay in the emergency department of a tertiary private hospital in the Philippines." Acta Medica Philippina, Vol. 52, No. 6, 2018, pp. 519-26.

- Bernstein, Edward, et al. "A public health approach to emergency medicine: Preparing for the twenty‐first century." Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 1, No. 3, 1994, pp. 277-86.

- Rondeau, KV, and Francescutti LH. "Health promotion and disease prevention attitudes of Canadian emergency physicians: Findings from a national study." Ontario, Canada, 2003.

- Rotter, Julian B. "Some problems and misconceptions related to the construct of internal versus external control of reinforcement." Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 43, No. 1, 1975, pp. 56-67.

- Mann, N. Clay. "Injury Prevention. Who, Me?" Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 3, No. 4, 1996, pp. 291-92.

- Hargarten, Stephen W., Lenora Olson, and David Sklar. "Emergency medicine and injury control research: past, present, and future." Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 4, No. 4, 1997, pp. 243-44.

- Kelen, G. D. "Public health initiatives in the emergency department: Not so good for the public health?" Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2008, pp. 194-97.

- Betz, Marian E., et al. "Public health education for emergency medicine residents." American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 41, No. 4, 2011, pp. S242-50.

- Clancy, Carolyn M., and John M. Eisenberg. "Emergency medicine in population-based systems of care." Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 30, No. 6, 1997, pp. 800-03.

- Taira, Breena R. "Public health interventions in the emergency Department: One resident's perspective." Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 61, No. 3, 2013, pp. 326-29.

- Hsieh, Yu‐Hsiang, et al. "Emergency medicine resident attitudes and perceptions of HIV testing before and after a focused training program and testing implementation." Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 16, No. 11, 2009, pp. 1165-73.