Research - International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences ( 2022) Volume 11, Issue 6

Presenting Symptoms, Vaccination Status and Association Comorbidities in Confirmed Cases of COVID-19 in King Salman Army Forces Hospital North West Region, Tabuk City KSA

Sarah Almutairi, Department of Family Medicine, King Salman Armed Forces Hospital, Tabuk, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Email: sara.f.mutairi@gmail.com

Received: 29-May-2022, Manuscript No. ijmrhs-22-65307; Editor assigned: 30-May-2022, Pre QC No. ijmrhs-22-65307 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Jun-2022, QC No. ijmrhs-22-65307 (Q); Revised: 14-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. ijmrhs-22-65307 (R); Published: 30-Jun-2022

Abstract

Background: Most commonly reported symptoms for COVID-19 patients are anosmia, dysgeusia, cough, myalgias, and headache, with no specific clinical features that can reliably distinguish COVID-19 from other respiratory infections. Objectives: To describe the most frequent presenting symptoms of COVID-19, guide case suspicion, based on clinical manifestations, and characterize case severity. Patients and Methods: This was a retrospective descriptive hospital-based research design conducted at the Armed Forces Hospitals, Northwestern Region, in Tabuk City, Saudi Arabia among all adult patients aged ≥ 18 years who were admitted as confirmed cases of COVID-19. A data collection sheet was utilized including patients’ demographic data, presenting symptom(s) and their severity, vaccination status, and a history of recent contact with any confirmed case. Results: A total of 300 patients with confirmed COVID-19 were included. Their age ranged from 18 and 85 years. Equally were distributed between males and females. History of travel in the last 14 days was mentioned by 9.7% of them while 71.3% reported contact with confirmed cases. Cough was the commonest reported symptom (49.3%), followed by fever (44%), headache (36.7%), sore throat (28.7%), and running nose (22%). Regarding vaccinated cases, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine ranked first (66%), followed by the AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine (23.9%) and both vaccines (8.1%). Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that patients who received a second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech or AstraZeneca Oxford vaccines were at lower risk for developing moderate/severe symptoms than those who received one dose, p=0.001 and 0.008; respectively. Conclusion: Most cases of confirmed COVID-19 infection were mild. The vast majority of the participants had received the COVID-19 vaccine. Of them, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine ranked first, followed by the AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine and both vaccines. Patients who received a second dose of either AstraZeneca Oxford or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines were at lower risk for developing moderate/severe symptoms than those who received one dose.

Keywords

COVID-19, Confirmed cases, Vaccines, Presenting symptoms, Severity

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging respiratory viral infection, caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. This disease was first reported in Wuhan City, Hubei Province (China) on December 13th, 2019 and was officially considered a pandemic by the World Health Organization in March 2020 [2]. In Saudi Arabia, the first confirmed case was reported on March 2nd, 2020 [3].

COVID-19 showed high rates of transmission. As of October 24th, 2021, the Worldometer reported 259,731,904 confirmed cases and 5,192,249 deaths worldwide, i.e., a 2% case fatality rate. In Saudi Arabia, there have been 549,590 confirmed cases, and 8,828 deaths, i.e., a 1.6% case fatality rate [4].

Several studies reported that several COVID-19 patients developed anosmia, or dysgeusia, suggesting that this symptom could be used as a screening tool to identify people with potential mild cases who could be recommended to self-isolate [5]. Also, other symptoms, (e.g., cough, myalgias, and headache) were most commonly reported. However, these symptoms may not be present, thus hindering case definition [6]. Moreover, other features including nausea, diarrhea, and sore throat were also well described [7,8]. Serious manifestations of infection include fever, cough, dyspnea, and infiltrates on chest imaging. Therefore, it has been concluded that there are no specific clinical features that can reliably distinguish COVID-19 from other viral respiratory infections [9].

The spectrum of symptomatic infection ranges from mild to critical; most infections are not severe [10-12]. Therefore, healthcare services should use a sensitive case definition, to adopt appropriate surveillance, prevention, and treatment actions [6]. In suspected cases, based on clinical symptoms and signs or previous contact with confirmed COVID-19 cases, it is recommended to use Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) to confirm the diagnosis [13].

Zitek noted that diagnostic tests are intended to be used at specific times of infection and, depending on the stage of the disease, may not be very accurate [14]. Therefore, assessing clinical signs and self-reported symptoms shown by infected people can help establish the healthcare flow and indicate the need to perform confirmatory tests [15]. Canas, et al. added that early reported symptoms allow timely self-isolation, urgent testing and management, and consequently better outcome [16].

The present study aims to describe the most commonly presenting symptoms of confirmed COVID-19 cases to guide case suspicion, based on clinical manifestations, characterize case severity, and addition to identify the detailed vaccination status of confirmed cases of COVID-19.

Subjects and Methods

This is a single-center study followed by a retrospective descriptive hospital-based research design conducted at the Armed Forces Hospitals, Northwestern Region, in Tabuk City, Saudi Arabia.

The study population includes all confirmed cases of COVID-19, who were admitted to the Armed Forces Hospital, Northwestern Region in Tabuk City during the period from March 2021 till November 2021. The minimum sample size was calculated according to Dahiru, et al., and correction for the population of the study, with a confidence level of 95% and p-value of 50%, the sample size accounted for 384 [17]. However, the sample size was increased to at least 400 patients to compensate for missing data.

The study included adult patients aged ≥ 18 years presenting to the study setting who proved by RT-PCR to have COVID-19 infection. Children are aged <18 years and those who were not confirmed to have COVID-19 were excluded from the study.

A data collection sheet has been designed and adapted from a previously published research work [18]. It included demographic data (age, gender, educational level, occupation, residence, smoking status, travel status in the last 14 days, and body mass index), presenting symptom(s) (no symptoms, fever, chills, cough, difficulty of breathing (dyspnea), running nose, sneezing, loss of smell, loss of taste, headache, muscle ache, sore throat, malaise, nausea and vomiting, and diarrhea), vaccination status (If yes, BNT162b2 mRNA (Pfizer-BioNTech) and/or ChAdOx1 nCoV19 adenoviral (Oxford-AstraZeneca) vaccines, comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, asthma, chronic lung disease, hematological disease, stroke, viral hepatitis B or C, liver cirrhosis, cancer, or others), and severity of symptom(s) (patients with COVID-19 were grouped according to the NIH into the following severity of illness categories [19]:

Asymptomatic

Individuals who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 using a virologic test or an antigen test but who have no symptoms that are consistent with COVID-19.

Mild

Individuals who have any of the various signs and symptoms of COVID-19 (e.g., fever, cough, sore throat, malaise, headache, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, loss of taste and smell) but who do not have shortness of breath, dyspnea, or abnormal chest imaging.

Moderate

Individuals who show evidence of lower respiratory disease during clinical assessment or imaging and who have an oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≥ 94% on room air at sea level.

Severe

Individuals who have SpO2 <94% on room air at sea level, a ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) <300 mm Hg, a respiratory rate >30 breaths/min, or lung infiltrates >50%.

Critical

Individuals who have respiratory failure, septic shock, and/or multiple organ dysfunction. In addition to the history of recent contact with a confirmed case.

After obtaining all the necessary official approvals, data of all registered patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were retrieved and recorded into an Excel sheet.

Collected data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM, SPSS version 26). Descriptive statistics (frequency and percentage for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables) were calculated. Tests of significance, (i.e., chi-square and Fischer exact tests for categorical variables) were applied to identify significant presenting symptoms associated with the severity of positive PCR results. Binary logistic regression was applied to design an equation for predictors of severity of a symptom of COVID-19. p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and Personal Characteristics

A total of 300 patients with confirmed COVID-19 were included in the study. Table 1 presents their demographic and personal characteristics. There are ranges between 18 and 85 years with a mean ± Standard Deviation (SD) of ± 11.9 years. Equally were distributed between males and females. Almost two-thirds (69.3%) were married and among married females, 5.8% were pregnant. Half of them were university graduates. Regarding their occupation, 33% were military persons whereas 34.7% were unemployed. The vast majority (99%) live in urban areas. Smoking was reported by 24.3% of them. History of travel in the last 14 days was mentioned by 9.7% of patients while most of them (71.3%) reported contact with confirmed cases.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||

| 18-40 | 217 | 72.3 |

| 41-60 | 74 | 24.7 |

| >60 | 9 | 3 |

| Range | 18-85 | |

| Mean ± SD | 34.8 ± 11.9 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 150 | 50 |

| Female | 150 | 50 |

| Marital status | ||

| Nor married | 92 | 30.7 |

| Married | 208 | 69.3 |

| Pregnancy* (n=104) | ||

| No | 98 | 94.2 |

| Yes | 6 | 5.8 |

| Educational level | ||

| Illiterate | 8 | 2.7 |

| Primary school | 16 | 5.3 |

| Intermediate school | 14 | 4.7 |

| Secondary school | 108 | 36 |

| University | 150 | 50 |

| Postgraduate | 4 | 1.3 |

| Occupation | ||

| Unemployed | 104 | 34.7 |

| Teacher | 25 | 8.3 |

| Administrative | 5 | 1.7 |

| Healthcare worker | 15 | 5 |

| Military | 99 | 33 |

| Others | 52 | 17.3 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 297 | 99 |

| Rural | 3 | 1 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Non smoker | 227 | 75.7 |

| Smoker | 73 | 24.3 |

| Travel status in the last 14 days | ||

| No | 271 | 90.3 |

| Yes | 29 | 9.7 |

| Contact with a confirmed case | ||

| No | 86 | 28.7 |

| Yes | 214 | 71.3 |

| *For married females | ||

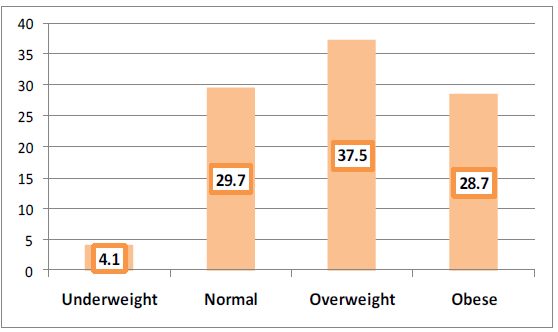

Most of the confirmed COVID-19 cases were either overweight (37.5%) or obese (28.7%) as seen in Figure 1.

Presenting Symptoms

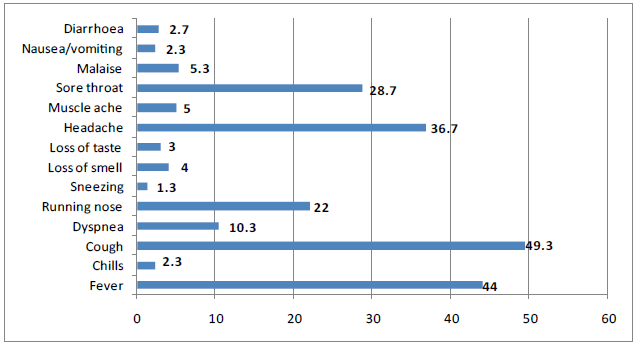

Figure 2 summarizes the presenting symptoms among confirmed COVID-19 cases. Cough was the commonest reported symptom (49.3%), followed by fever (44%), headache (36.7%), sore throat (28.7%), and running nose (22%). Minorities reported gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea (2.7%) and nausea/vomiting (2.3%).

Comorbidities

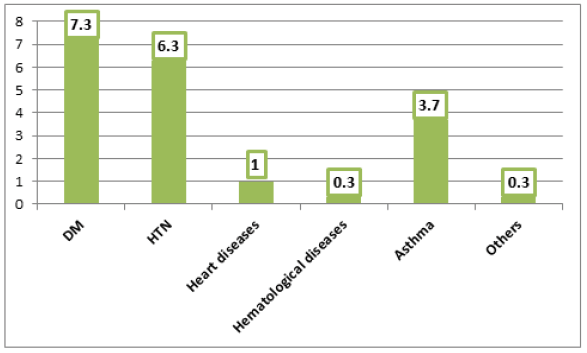

It is realized from Figure 3 that diabetes (7.3%), hypertension (6.3%), and bronchial asthma (3.7%) were the commonest reported comorbidities among COVID-19 cases. Overall, 14% of patients had co-morbid diseases.

Vaccination Status

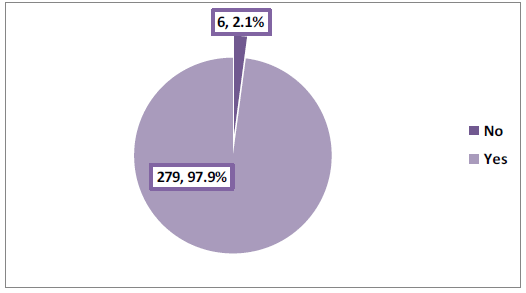

Among cases with valid information about vaccination status (n=285), the majority (97.9%) had the COVID-19 vaccine as illustrated in Figure 4. In vaccinated cases, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine ranked first (66%), followed by the AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine (23.9%) and both vaccines (8.1%) (Table 2).

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine | 188 | 66 |

| One dose | 102 | 54.3 |

| Two doses | 79 | 42 |

| Three doses | 7 | 3.7 |

| AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine | 68 | 23.9 |

| One dose | 56 | 82.4 |

| Two doses | 12 | 17.6 |

| Both | 23 | 8.1 |

Severity of COVID-19 Symptoms

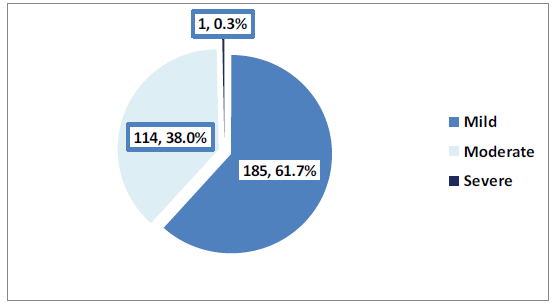

As shown in Figure 5, in 61.7% of cases, the symptoms were mild while moderately severe cases were observed in 38% of cases and one case was described as severe and died.

Moderate/severe cases were more likely to affect older patients (aged over 60 years) than younger patients (18-40 years) (77.8% vs. 35%), p=0.021. Teachers and administrators had the highest rate of moderate/severe symptoms (60%) whereas military persons (37.4%) and others (15.4%) had the lowest rates, p=0.002. All rural residents compared to only 37.7% of urban residents had moderate/severe symptoms, however, this difference was borderline statistically insignificant (p=0.055). Overweight patients had the highest rate of moderate/severe symptoms (48.2%) while underweight subjects had the lowest rate (25%), p=0.025. More than half (58.1%) of patients with no history of contact with confirmed cases compared to 30.4% of those who reported such history had moderate/severe symptoms, p<0.001. All cases with a history of heart disease compared to only 37.7% of those without such history had moderate/ severe symptoms, however, this difference was borderline statistically insignificant (p=0.055). Cases who received the COVID-19 vaccine were less likely to have moderate/severe symptoms compared to their peers (36.9% vs. 83.3%), p=0.031. Moderate/severe symptoms were less likely to occur with the AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine compared to the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (25% vs. 36.9%), p=0.028. Cases that received one dose of either AstraZeneca Oxford or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines were less likely to have moderate/severe symptoms compared to those that received more vaccine doses, p=0.003 and <0.001, respectively (Table 3).

| COVID-19 severity | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mild | Moderate to severe | ||

| N=185 N (%) | N=115 N (%) | ||

| Age in years | |||

| 18-40 (n=217) | 141 (65.0) | 76 (35.0) | 0.021* |

| 41-60 (n=74) | 42 (56.8) | 32 (43.2) | |

| >60 (n=9) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male (n=150) | 95 (63.3) | 55 (36.7) | 0.553* |

| Female (n=150) | 90 (60.0) | 60 (40.0) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Nor married (n=92) | 57 (62.0) | 35 (38.0) | 0.945* |

| Married (n=208) | 128 (61.5) | 80 (38.5) | |

| Pregnancy* (n=104) | |||

| No (n=98) | 60 (61.2) | 38 (38.8) | 0.577** |

| Yes (n=6) | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Illiterate (n=8) | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | 0.167* |

| Primary school (n=16) | 8 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| Intermediate school (n=14) | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | |

| Secondary school (n=108) | 74 (68.5) | 34 (31.5) | |

| University (n=150) | 87 (58.0) | 63 (42.0) | |

| Postgraduate (n=4) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed (n=104) | 59 (56.7) | 45 (43.3) | 0.002* |

| Teacher (n=25) | 10 (40.0) | 15 (60.0) | |

| Administrative (n=5) | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Healthcare worker (n=15) | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | |

| Military (n=99) | 62 (62.6) | 37 (37.4) | |

| Others (n=52) | 44 (84.6) | 8 (15.4) | |

| Residence | |||

| Urban (n=297) | 185 (62.3) | 112 (37.7) | 0.055** |

| Rural (n=3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100) | |

| Body mass index | |||

| Underweight (n=12) | 9 (75.0) | 3 (25.0) | 0.025* |

| Normal (n=87) | 57 (65.5) | 30 (34.5) | |

| Overweight (n=110) | 57 (51.8) | 53 (48.2) | |

| Obese (n=84) | 60 (71.4) | 24 (28.6) | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Non-smoker (n=227) | 140 (61.7) | 87 (38.3) | 0.996* |

| Smoker (n=73) | 45 (61.6) | 28 (38.4) | |

| Travel status in last 14 days | |||

| No (n=271) | 163 (60.1) | 108 (39.9) | |

| Yes (n=29) | 22 (75.9) | 7 (24.1) | 0.098* |

| Contact with a confirmed case | |||

| No (n=86) | 36 (41.9) | 50 (58.1) | <0.001* |

| Yes (n=214) | 149 (69.6) | 65 (30.4) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |||

| No (n=278) | 176 (62.2) | 105 (37.8) | 0.475* |

| Yes (n=22) | 12 (54.5) | 10 (45.5) | |

| Hypertension | |||

| No (n=281) | 177 (63.0) | 104 (37.0) | 0.070* |

| Yes (n=19) | 8 (42.1) | 11 (57.9) | |

| Bronchial asthma | |||

| No (n=289) | 180 (62.3) | 109 (37.7) | 0.260* |

| Yes (n=11) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | |

| Heart diseases | |||

| No (n=297) | 185 (62.3) | 112 (37.7) | 0.055** |

| Yes (n=3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100) | |

| COVID-19 vaccination (n=285) | |||

| No (n=6) | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | 0.031** |

| Yes (279) | 176 (63.1) | 103 (36.9) | |

| Type of vaccine (n=279) | |||

| Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine (n=188) | 113 (60.1) | 75 (36.9) | 0.028* |

| AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine (n=68) | 51 (75.0) | 17 (25.0) | |

| Both (n=23) | 11 (47.8) | 12 (25.2) | |

| Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine | |||

| One dose (n=102) | 87 (85.3) | 15 (14.7) | <0.001 |

| Two doses (n=79) | 25(31.6) | 54 (68.4) | |

| Three doses (n=7) | 1 (14.3) | 6 (85.7) | |

| AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine | |||

| One dose (n=56) | 46 (82.1) | 10 (17.9) | 0.003 |

| Two doses (n=12) | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | |

| *Chi-square test; **Fischer Exact test | |||

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that patients who received a second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine were at lower risk for developing moderate/severe symptoms than those who received one dose (Adjusted Odds Ratio “AOR”=0.03, 95% Confidence Interval “CI”: 0.001-0.24), p=0.001. Similarly, patients who received a second dose of the AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine were at lower risk for developing moderate/severe symptoms than those who received one dose (AOR=0.16, 95% CI: 0.04-0.62), p=0.008. History of vaccination, type of the vaccine, history of contact with a confirmed case, occupation, body mass index, and age was not significantly associated with COVID-19 symptoms` severity after controlling for confounding effect (Table 4).

| B | SE | AOR | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of vaccine | |||||

| No | 1 | --- | |||

| Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine | -1.455 | 1.229 | 0.23 | 0.02-2.60 | 0.236 |

| AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine | -1.705 | 1.158 | 0.18 | 0.02-1.76 | 0.141 |

| Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine | |||||

| One dose | 1 | --- | |||

| Two doses | -3.619 | 1.118 | 0.03 | 0.001-0.24 | 0.001 |

| Three doses | -1.099 | 1.108 | 0.33 | 0.04-2.92 | 0.321 |

| AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine | |||||

| One dose | 1 | 1 | |||

| Two doses | *1.818 | 0.682 | 0.16 | 0.04-0.62 | 0.008 |

| B: Slope; SE: Standard Error; AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; CI: Confidence Interval Terms of vaccination, contact with a confirmed case, occupation, body mass index, and age were removed from the final model |

|||||

Discussion

In the current study, the most frequently reported presenting symptoms among confirmed COVID-19 cases were cough, fever, headache, sore throat, and running nose. However, minorities reported gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea and nausea/vomiting as well as loss of taste and loss of smell. Iser, et al., in their narrative review, reported that the commonly reported clinical spectrum of COVID-19 among Brazilians was fever, cough, and dyspnea [6]. Moreover, gastrointestinal symptoms and dysgeusia or anosmia have been reported in mild cases, while dyspnea was frequent in severe and fatal cases. In Myanmar, fever, cough, and loss of smell were the most common symptoms [18]. However, numerous studies reported that the commonest presenting symptoms of COVID-19 infection were sore throat, fatigue, shortness of breath, and rhinorrhea [20-24]. Zahra, et al. reported in their systematic review that symptoms of anosmia and dysgeusia were frequently reported by COVID-19-positive patients; particularly females and younger patients [2]. Variation in the presenting symptoms between various studies carried out in different geographical areas could be related to genetic predisposition as well as cultural factors [24].

In the present study and following others, there was no gender difference regarding the severity of COVID-19 symptoms [25,26]. However, some others reported female predominance in studies carried out in China, the USA, and Germany while others reported male predominance in studies carried out in Thailand, Singapore, and China [18,20,21,27-29].

In the current study, diabetes, hypertension, and bronchial asthma were the commonest reported comorbidities among COVID-19 confirmed cases and overall, 14% of patients had co-morbid diseases. Higher rates were reported in studies carried out in Myanmar (37.8), Thailand (25.0%), and Singapore (28.3%) [18,21,28]. However, a comparable figure was observed in a study carried out in China (15.8%) [25]. This variation between studies could be explained by differences between them in the prevalence of chronic diseases across age, gender distribution, as well as geographic area.

In line with the present study, numerous studies revealed that hypertension and diabetes mellitus were the commonest reported co-morbid diseases in COVID-19 patients [18,24,25,27,29,34].

In the present study, 61.7% of cases were regarded as mild while 38% were regarded as moderate and only one case was described as severe and died. Usually, the high rate of asymptomatic or mild cases is a reflection of good practice in case finding, tracing of close contact as well as massive surveillance of suspected COVID-19 cases [18]. However, on the other hand, having a high rate of asymptomatic or mild cases might help in the rapid spread of infection [30].

In a univariate analysis in this study, older patients were more likely to have moderate/severe symptoms. However, after controlling for the confounders in multivariate logistic regression analysis, this effect disappeared. The association between the severity of COVID-19 symptoms and older age has been observed in several studies [18,20,21,25,27]. The disappearance of the association between older age and severity of COVID-19 symptoms in multivariate analysis in this study could be attributed to the effect of COVID-19 vaccination which was not included in other studies, which could upper-handed the effect of other factors including older age.

In the univariate analysis and line with other studies carried out in Thailand, Germany, and China, overweight patients were more likely to have moderate/severe symptoms [21,22,27]. However, after controlling for the confounders in multivariate logistic regression analysis, this effect disappeared in the present study.

Also, in univariate analysis, cases who received the COVID-19 vaccine were less likely to have moderate/severe symptoms compared to their peers. However, after controlling for the confounders in multivariate logistic regression analysis, this effect disappeared. The vast majority of the participants in this study had received the COVID-19 vaccine (97.9%). Of them, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine ranked first (66%), followed by the AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine (23.9%) and both vaccines (8.1%). Even after controlling for the effect of confounding in the present study, patients who received a second dose of either AstraZeneca Oxford or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines were at lower risk for developing moderate/severe symptoms than those who received one dose. Hall V, et al. observed that two doses of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine were associated with high protection against COVID-19 infection; however, this protection was short-term as it is reduced considerably after 6 months. However, infection-acquired immunity accompanied by vaccination remained high for more than a year after infection [31]. Also, Antonelli M, et al. concluded that the rate and severity of COVID-19 infection reduced; particularly in elderly patients after first or second COVID-19 vaccinations with Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2), ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, or mRNA-1273 [32]. Additionally, numerous studies confirmed that nearly all individual symptoms of COVID-19 were less frequent in vaccinated versus unvaccinated patients, and more patients in the vaccinated than in the unvaccinated groups were asymptomatic [33-38].

The present study has some limitations that should be mentioned. First of all, because of the retrospective observational design of the present study, it was subjected to selection bias. Second, because the fact that this study was carried out in only one center, the generalizability of findings over other health care facilities is questionable. Third, some hematological and biochemical markers like hemoglobin level, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, D-dimer, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST and prothrombin time that might influence the severity of disease were not investigated in this study.

Conclusion

In conclusion, most cases of confirmed COVID-19 infection were mild. The most frequently reported presenting symptoms among them were cough, fever, headache, sore throat, and running nose. The vast majority of the participants in this study had received the COVID-19 vaccine. Of them, the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine ranked first, followed by the AstraZeneca Oxford vaccine and both vaccines. Patients who received a second dose of either AstraZeneca Oxford or Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines were at lower risk for developing moderate/severe symptoms than those who received one dose. Based on the present study`s findings, we recommended vaccination of people with second and booster doses of the vaccine, particularly in more vulnerable groups. We also recommended carrying out a further longitudinal study with a large sample size to achieve a higher strength of association between various factors and the severity of COVID-19 infection.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Shah, Ain Umaira Md, et al. "COVID-19 outbreak in Malaysia: Actions taken by the Malaysian government." International Journal of Infectious Diseases, Vol. 97, 2020, pp. 108-16.

Google scholar Crossref - Zahra, Syeda Anum, et al. "Can symptoms of anosmia and dysgeusia be diagnostic for COVID‐19?" Brain and Behavior, Vol. 10, No. 11, 2020, p. e01839.

Google scholar Crossref - Nurunnabi, Mohammad. "The preventive strategies of COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia." Journal of Microbiology, Immunology, and Infection, Vol. 54, No. 1, 2021, pp. 127-28.

Google scholar Crossref - Worldometer. "COVID live updates-Coronavirus Statistics."

- Menni, Cristina, et al. "Loss of smell and taste in combination with other symptoms is a strong predictor of COVID-19 infection." Nature Medicine, Vol. 26, 2020, pp.1037-40.

Google scholar Crossref - Iser, Betine Pinto Moehlecke, et al. "Suspected COVID-19 case definition: A narrative review of the most frequent signs and symptoms among confirmed cases." Epidemiology and Health Services, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2020, p. e2019354.

Google scholar Crossref - Goyal, Parag, et al. "Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in New York city." New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 382, No. 24, 2020, pp. 2372-74.

Google scholar Crossref - Jin, Xi, et al. "Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of Coronavirus-Infected Disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms." Gut, Vol. 69, No. 6, 2020, pp. 1002-09.

Google scholar Crossref - McIntosh, Kenneth. "COVID-19: Clinical features." Uptodate, 2021.

- Huang, Chaolin, et al. "Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China." The Lancet, Vol. 395, No. 10223, 2020, pp. 497-506.

Google scholar Crossref - Wang, Dawei, et al. "Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China." JAMA, Vol. 323, No. 11, 2020, pp. 1061-69.

Google scholar Crossref - Yang, Xiaobo, et al. "Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A single-centered, retrospective, observational study." The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, Vol. 8, No. 5, 2020, pp. 475-81.

Google scholar Crossref - Assaker, Rita, et al. "Presenting symptoms of COVID-19 in children: A meta-analysis of published studies." BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia, Vol. 125, No. 3, 2020, pp. e330-31.

Google scholar Crossref - Zitek, Tony. "The appropriate use of testing for COVID-19." Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2020, pp. 470-72.

Google scholar Crossref - Tolia, Vaishal M., Theodore C. Chan, and Edward M. Castillo. "Preliminary results of initial testing for coronavirus (COVID-19) in the emergency department." Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2020, pp. 503-06.

Google scholar Crossref - Canas, Liane S., et al. "Early detection of COVID-19 in the UK using self-reported symptoms: A large-scale, prospective, epidemiological surveillance study." The Lancet Digital Health, Vol. 3, No. 9, 2021, pp. e587-98.

Google scholar Crossref - Dahiru, T., A. Aliyu, and T. S. Kene. "Statistics in medical research: Misuse of sampling and sample size determination." Annals of African Medicine, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2006, pp. 158-61.

Google scholar - Htun, Ye Minn, et al. "Initial presenting symptoms, comorbidities and severity of COVID-19 patients during the second wave of epidemic in Myanmar." Tropical Medicine and Health, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2021, pp. 1-10.

Google scholar Crossref - COVID, NIH. "Treatment guidelines. Clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection." 2021.

Google scholar Crossref - Vaughan, Laura, et al. "Relationship of socio-demographics, comorbidities, symptoms and healthcare access with early COVID-19 presentation and disease severity." BMC Infectious Diseases, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2021, pp. 1-10.

Google scholar Crossref - Pongpirul, Wannarat A., et al. "Clinical course and potential predictive factors for pneumonia of adult patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A retrospective observational analysis of 193 confirmed cases in Thailand." PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, Vol. 14, No. 10, 2020, p. e0008806.

Google scholar Crossref - Rao, Xinrui, et al. "The importance of overweight in COVID-19: A retrospective analysis in a single center of Wuhan, China." Medicine, Vol. 99, No. 43, 2020.

Google scholar Crossref - Lee, Hyun Woo, et al. "Clinical implication and risk factor of pneumonia development in mild coronavirus disease 2019 patients." The Korean Journal of Internal Medicine, Vol. 36, No. 1, 2021, pp. 1-10.

Google scholar Crossref - Feng, Zhichao, et al. "Early prediction of disease progression in COVID-19 pneumonia patients with chest CT and clinical characteristics." Nature Communications, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-9.

Google scholar Crossref - Li, Yanli, et al. "Asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with non-severe Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) have similar clinical features and virological courses: A retrospective single center study." Frontiers in Microbiology, Vol. 11, 2020, p. 1570.

Google scholar Crossref - Zhang, Shan-Yan, et al. "Clinical characteristics of different subtypes and risk factors for the severity of illness in patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang, China." Infectious Diseases of Poverty, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-10.

Google scholar Crossref - Sacco, Vanessa, et al. "Overweight/obesity as the potentially most important lifestyle factor associated with signs of pneumonia in COVID-19." PloS One, Vol. 15, No. 11, 2020, p. e0237799.

Google scholar Crossref - Puah, Ser Hon, et al. "Clinical features and predictors of severity in COVID-19 patients with critical illness in Singapore." Scientific Reports, Vol. 11, No. 1, 2021, pp. 1-11.

Google scholar Crossref - Liu, Xue-qing, et al. "Clinical characteristics and related risk factors of disease severity in 101 COVID-19 patients hospitalized in Wuhan, China." Acta Pharmacologica Sinica, Vol. 43, No. 1, 2022, pp. 64-75.

Google scholar Crossref - Li, Ruiyun, et al. "Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)." Science, Vol. 368, No. 6490, 2020, pp. 489-93.

Google scholar Crossref - Hall, Victoria, et al. "Protection against SARS-CoV-2 after Covid-19 vaccination and previous infection." New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 386, No. 13, 2022, pp. 1207-20.

Google scholar Crossref - Antonelli, Michela, et al. "Risk factors and disease profile of post-vaccination SARS-CoV-2 infection in UK users of the COVID Symptom Study app: A prospective, community-based, nested, case-control study." The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Vol. 22, No. 1, 2022, pp. 43-55.

Google scholar Crossref - Baden, Lindsey R., et al. "Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine." New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 384, 2020, pp. 403-16.

Google scholar Crossref - Skowronski, Danuta M., and Gaston De Serres. "Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine." New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 384, No. 16, 2021, pp. 1576-77.

Google scholar - Voysey, Merryn, et al. "Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: An interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK." The Lancet, Vol. 397, No. 10269, 2021, pp. 99-111.

Google scholar Crossref - Menni, Cristina, et al. "Vaccine side-effects and SARS-CoV-2 infection after vaccination in users of the COVID Symptom Study app in the UK: A prospective observational study." The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Vol. 21, No. 7, 2021, pp. 939-49.

Google scholar Crossref - Bernal, Jamie Lopez, et al. "Effectiveness of the Pfizer-BioNTech and Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccines on COVID-19 related symptoms, hospital admissions, and mortality in older adults in England: Test negative case-control study." BMJ, Vol. 373, 2021.

Google scholar Crossref - Haas, Eric J., et al. "Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: An observational study using national surveillance data." The Lancet, Vol. 397, No. 10287, 2021, pp. 1819-29.

Google scholar Crossref